HOME | Contents | Introduction | The Creation | The Garden of Eden | The Flood | The Historical Deluge | The Tower of Babel

HOME | Contents | Introduction | The Creation | The Garden of Eden | The Flood | The Historical Deluge | The Tower of Babel

MODERN archaeology begins with Napoleon Bonaparte,

who included a corps of savants in his Egyptian expeditionary force of 1798.

The British fleet on their way to France intercepted his ships, loaded with antiques,

and most of the booty found its way to the British Museum, where

it may still be viewed.

Nearly forty years, however, were to elapse before the decipherment of the Rosetta Stone

(by the

Englishman Young and the French Champollion)

in 1830 unravelled the secret of the Egyptian hieroglyphics,

and the inscriptions on the idols which had remained dumb for over two thousand years were made to speak.

[It was the Rosetta Stone

which, with its parallel columns in Egyptian and Greek,

provided the clue to the decipherment of hieroglyphics. W.O.P.250.]

The excavations proceeded

[For Egyptian antiquities in general see W.O. P., passim.],

discovery after discovery

stirred the imagination of the public

as the almost incredibly ancient past was brought to life,

and

from the first a very special interest attached to those discoveries which seemed to throw light upon the Bible.

More thrilling even than the Egyptian excavations, from the

Biblical point of view,

were those of Botta and Sir Henry Layard in Mesopotamia towards the middle of the century,

when the

long-forgotten sites of Nineveh, Babylon,

and even the Tower of Babel (so it was believed) were found.

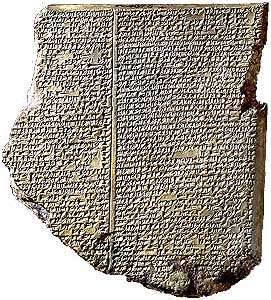

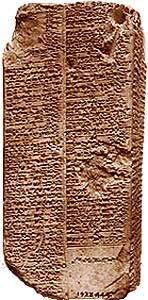

But to scholars the

greatest achievement was the recovery of a whole library of Assyrian books in the palace of Ashur-banipal at Nineveh.

True, the

books were written on clay tablets in a queer-looking,

wedge-shaped script that no one could read,

but what had been achieved with

hieroglyphics must be possible with cuneiform too.

The decipherment of cuneiform,

in the absence of a Mesopotamian Rosetta Stone,

proved a tedious and difficult

business,

but at length the genius of Rawlinson succeeded where many had failed,

and in 1850 the first long cuneiform

inscription,

that of the Black Obelisk,

was translated into English,

revealing the first Biblical name to be discovered by

archaeologymdash;

'Jehu the son of Omri',

King of Israel.

Excitement rose still higher when Rassam discovered at Nineveh in 1854 some

fragments of an ancient Babylonian legend of Creation strongly reminiscent

of that in the Book of Genesis.

And when George Smith deciphered in 1871 the

beginning of a cuneiform story of the Flood the Daily Teleraph newspaper

sent him out to Nineveh immediately with a thousand pounds in his pocket

to find the other half of the story.

In 1873 the whole of the now famous Gilgamesh Flood Epic was

published,

and George Smith's Chaldaean Account of Genesis became a Victorian

bestseller.

Its gist has been embodied in

every commentary on Genesis ever since,

a fact which will excuse the somewhat cursory treatment of the subject here.

[e.g. W. H. Bennett, Genesis (Century Bible).

For an elaborate discussion see Jeremias, The Old Testament in the Light

of the Ancient East (1911),

together with more recent discoveries discussed in S.

Langdon, Sumerian Epic of Creation (1915),

and indeed any work on Biblical archaeology.]

top

It will be noticed from the above scriptural references that there are two different versions of the Creation

Story,

an early form (J)

and a much later one (P).

A similar phenomenon is found in the many Babylonian versions which have come

to light.

The Gilgamesh Epic discovered by George Smith is written in a highly developed

metrical form

dating only, perhaps, from the eighth century,

but fragments of far older forms of the legend have been discovered.

At Sippar was found a fragment self-dated as 'the eleventh year of King Ammizaduga' (1966 BC);

at Nippur a tablet dated by its discoverer, Hilprecht, at 2100 BC;

and oldest

of all the famous six-column tablet

published by S. Langdon in 1915,

known as the Sumerian Epic of

the Creation and Paradise,

of a date perhaps as early as 3000 BC.

The

latter, despite its antiquity, is in a highly literary metrical form,

indicating an antecedent original even more archaic,

so that

we may well suppose that the archetype of the Creation Story so familiar to us from Genesis is almost as old as civilization

itself.

The publication of these Babylonian legends has made it abundantly clear that they have a definite

blood-relationship with those in the Bible.

There are, of course, Creation and Flood stories from all over the world

[Collected in Frazer's Folklore in the Old Testament (1918).],

and many of them have points in

common with Genesis.

But the resemblances between the Biblical and the Babylonian versions are much more remarkable than that,

as we shall see.

So that even without the tradition that the Hebrew people originally lived in Babylonia,

we should have been

forced to notice a distinct Babylonian element in their earliest culture.

Yet the differences between the Biblical and the extant Babylonian legends are

sufficiently marked to indicate other influences in the development from the original archetype.

It may be that the Hebrew version

of the legend is older even than the Sumerian in some of its details,

and Yahuda has produced weighty evidence to show a

predominant Egyptian colouring of the literary form assumed by these legends in the Pentateuch.

In any case, the religious

genius of the Hebrews has raised the original stories to a spiritual and moral level as far above the Babylonian versions as

Jerusalem is above the muddy lowlands of Chaldaea.

'Archaeology demonstrates that though the religion of Israel was built upon the

same material foundation as that of other Semitic peoples,

it rose immeasurably above them:

it assumed as it developed a unique

character,

and in the hands of its inspired teachers became the expression of great spiritual realities

such as has been without

parallel in any other nation of the earth.'

[S. R. Driver, Modern Research as illustrating the

Bible (Schweich Lecture, 1908).]

The Babylonian version of the Creation best preserved to us

is contained in the Seven Tablets of Creation,

whose central figure is the semi-divine hero Gilgamesh.

It begins with the Era before creation,

When the heavens were not yet named,

Beneath the earthmdash;not yet named by name.

It then proceeds to describe a battle among the gods,

the bone of

contention being Marduk's design to make a world.

Eventually Marduk triumphs,

slays his chief opponent Tiamat,

and cuts her body

in two pieces to make what the Bible calls a 'firmament'

dividing the new earth and heaven from the destructive waters of Chaos

above and below.

Here it has been suggested that the Babylonian and the Hebrew versions reveal a common origin:

the name Tiamat

has even been preserved,

perhaps,

[Yahuda denies this:

the Hebrew Tehom = Tamtu (ocean),

not Tiamat:

'The repeated attempt to establish a linguistic dependence of these stories

on Akkadian is completely beside the mark.']

in the Hebrew word for the 'Deep', viz. Tehom.

The Epic runs:

Marduk cleft Tiamat in two like a fish:

The half of her he raised up, and made a covering for the heavens.

He pushed a bolt before, placed watchers here,

Commanded them not to let the waters out.

So the heavens he created.

Tiamat in Babylonian legend is frequently represented as a huge dragon, or as

accompanied by dragons.

We find many allusions to this in the Bible:

for instance,

[The quotation from Ps.74

appears almost verbatim in the Ras Shamra tablets. See p.87.].

The very name Leviathan, or Labbu, appears in the

inscriptions:

In heaven the gods ask in haste,

Who will go and kill Labbu?

He let his clouds rise up,

And slew Labbu.

After this, the Babylonian like the Biblical version goes on to describe the creation of the heavenly bodies:

He prepared stations for the great gods,

As stars like to them he placed the constellations.

He lit up the moon to rule the night,

He ordained it as a night body to mark the days:

Monthly for ever to go forth giving light to the land.

At the beginning of the month beaming forth with horns,

To determine six days:

On the seventh day the disk shall be half.

Possibly in the foregoing reference to the phases of the moon

we find the rudiments

of a six-day working week and a Sabbath.

A fragment has indeed been found marking out the seventh day as one for special

observance:

Seventh Day, Nubattum, an Evil Day:

Cooked flesh he shall not eat: he shall not change his coat:

He shall not put on clean clothes:

He shall pour no libation:

No oracle shall speak.

The physician shall not heal the sick.

On this day all business is forbidden.

If this unlucky day was indeed the forerunner of the Sabbath, it certainly

furnishes, as Jastrow observes,

'another illustration of how it came about that the Babylonian and the Hebrew,

starting out with

so much in common,

should have ended by having so little in common'.

[M. Jastrow, Hebrew and

Babylonian Tradition (1914).]

The actual name Sabbath has been found in the tablets,

as Shabbatum,

'a Day of Peace of Heart for the gods'.

Possibly it was identical with Shappatu,

the fourteenth day of the month,

the day of the

Full Moon.

It may be that here,

rather than in Nubattum,

we have the germ of the Sabbath,

but on the whole it would seem

that our 'Day of Rest and Gladness' is a distinctively Hebrew institution.

In the Babylonian version of the creation of Man there are phrases reminiscent of the Biblical

bone of my bones and flesh of my flesh

(Gen.ii.33 J).

[Yahuda gives some striking

examples of the use of this phrase in Egyptian.

The creation of woman out of Adam's rib is peculiarly in keeping with Egyptian

ideas.]

Marduk said,

Blood will I take,

and bone will I build,

Creating mankind.

In the Sumerian legend the Mother-goddess Mama creates a man 'with the help of Enlil',

lord of the gods:

with which we compare the Biblical

I have gotten a man with the help of the lord

(Gen.iv.1 J).

We also find traces of the striking phrase

Let us make man in our image ...

in the image of God created He him

(Gen.i.26 P),

as for example:

In accordance with the incantation

Design a form that man may bear:

The man like Ninib in form,

The woman like Nintud in form shall be.

(Sumerian Hymn to Aruru.)

And again in the Gilgamesh Epic:

Thou, Aruru, hast been created by Gilgamesh:

Now make his counterpart.

When Aruru heard this, she made in her heart a counterpart of Anu.

Such, comparing Babylonian and Biblical Creation stories, are some of the

resemblances,

the number of which could doubtless be considerably enlarged if we possessed the former in their entirety.

top

Previous to the discovery of the Sumerian Epic of Paradise it was questioned whether

the Garden of Eden had any very close parallel in Babylonian legend [It should be noticed that where

there is no risk of confusion we use the term 'Babylonian' in its geographical rather than racial sense.].

There existed

indeed examples of the so-called 'Adam and Eve Seal',

supposed by some to portray the Fall.

On opposite sides of a fruit-bearing tree sit two figures, clothed, and one of them hatted.

On the extreme left is a serpent standing on the tip of its tail.

The imagery seems confused, if the Story of Paradise is

intended,

but the seals are now generally taken to represent an episode in the Gilgamesh Epic,

where Utnapishtim and his wife

assisted by a serpent guard the tree of life against the Hero's depredations.

There may, of course, be some remote connexion with

the trees of Eden.

The Sumerian Epic, however, forms a definite link.

Here for the first time we find

Creation connected, as in the Bible, with the Flood,

and the Flood with the sinfulness of Man.

The Age of Innocence is thus described, in language reminiscent of Isaiah:

In Dilmun, the Garden of the gods,

Where Enki with his consort lay,

That place was pure, that place was clean,

The lion slew not,

The wolf plundered not the lambs,

The dog harried not the kids in repose,

The birds forsook not their young,

The doves were not put to flight.

There was no disease nor pain,

No lack of wisdom among princes,

No deceit or guile.

But for some reason ('which is all too briefly defined', says

Langdon).

[S. Langdon, Sumerian Epic of Creation and Paradise (1915).]

Enki became

dissatisfied with man, and resolved to overwhelm him in a flood.

Then follows the story of the Flood, with which we shall deal

later,

and after the Flood (not before it, as in the Bible) we find a solitary survivor,

Tag-Tug [Tag-Tug (Sumerian for. Rest) = Noah (Hebrew for Rest).], back in the Garden.

He is

told he may eat of the trees of the Garden:

My king, as to the fruit-bearing plants

He shall pluck, he shall eat.

But there is one tree of which he may not eat, on pain of a curse:

My king the cassia plant approached:

He plucked, he ate.

Then Ninharsag in the name of Enki

Uttered a curse:

The face of Life, until he dies, Shall he not see.

Thus death and disease enter into Eden:

My brother, what of thee is ill?

My pastures are distressed,

My flocks are distressed,

My mouth is distressed,

My health is ill.

Such is the tragic end of the Legend of Dilmun.

It is the story of

a Paradise on earth, of a forbidden tree, of a Happiness that was lost.

But when we look for anything corresponding to the

strong moral element underlying the Biblical narrative, we look in vain.

[Yahuda perceives a

definitely Egyptian setting in the Paradise story:

the Garden is evidently (he thinks) an oasis in the Nile lands.]

top

It is when we come to the Flood story that the resemblances between the Biblical

account

[For details of the very interesting documentary analysis see the commentaries.]

and

the Babylonian become positively startling, as will be seen by the parallel columns set out below.

Here the relevant passages of

the Revised Version are reproduced in their correct sequence,

but to make the parallelism clearer the order of the Babylonian text

is slightly varied,

and fragments from non-Gilgamesh tablets (bracketed) have been inserted.

| THE BIBLE | BABYLONIAN TRADITION |

|---|---|

Genesis vi.5ff. |

[At a council of the Gods, Ea unfolded his design] |

And the LORD saw that the wickedness of man was great in the

earth, and that every imagination of the thoughts of his heart was only evil continually.

|

Ea opened his mouth when he spake, and said unto me his servant:

|

Make thee an ark of gopher wood, |

O man of Shurippak, son of Ubaratutu, |

And this is how thou shall make it: |

The ship which thou shalt build, |

And I, behold, |

Upon you shall the gods bring rain ... (making the animals and?) birds a prey to

fishes. |

And thou shall come into the ark, |

Bring in hither thy corn, thy possessions and goods, thy wife, thy male and

female family, the artisans, cattle of the field, beasts of the field, as many as eat green food.

|

In the six hundredth year of Noah's life ... |

So soon as something of the dawn appeared, |

In the selfsame day entered Noah and (his family), |

With all that I had I filled the ship, |

And the LORD shut him in. |

I entered into the ship and shut my door. |

And the waters prevailed, and increased greatly upon the earth;

|

The waters rose above the mountain, |

The gods were fearful of the stormy flood ... |

|

And all flesh died that moved upon the earth ... |

|

And God made a wind to pass over the earth, |

Six days and six nights lasted the wind, |

When the seventh day came the hurricane ceased, |

|

And the ark rested ... upon the mountains of Ararat. |

The land arose, |

And the waters decreased continually ... |

|

And it came to pass at the end of forty days, |

I opened the hatchway, |

And he sent forth a raven, and it went forth to and fro, until the waters were dried up from off the earth.

|

When the seventh day came, |

And Noah went forth ...out of the ark. |

Then let I out all to the four winds. |

And Noah builded an altar unto the LORD; ... |

I made a libation on the summit of the mountain, |

And the LORD said in his heart, |

[Said Ea] ,These days by the ornament of my neck I will not forget, I will

think upon these days, I will not forget them for ever. The gods may draw nigh to the libation,

|

While the earth remaineth, |

Why hast thou stirred up a storm flood? |

And God blessed Noah and his sons, and said unto them.

|

He grasped my hand, led me off. |

These parallel columns must be left to speak for themselves in a work that does not pretend to be a treatise

on Biblical literature.

top

To the Deluge as an historical fact, marking an epoch in local history, there are

several references in the Babylonian tablets;

and the actual names of the kings (or dynasties) which reigned before the Flood are

preserved in a fairly consistent tradition.

Thus the Blundell Prism

[W-B. 444 in the

Ashmolean Museum. See Oxford Edition of Cuneiform Texts, vol. ii (S. Langdon,

1923).]

concludes its list of eight pre-diluvian monarchs with the words:

At Surippak Ubardudu was (eighth) king,

And ruled 18,600 years: one king, five cities.

Eight kings, they ruled 241,200 years.

The Deluge came up upon the land.

After the Deluge had come, the rulership which descended from heaven,

At Kish there was the rulership, &c.

A somewhat later form of the tradition,

long known to us through the writings of Berosus,

and now corroborated by a fragment in the Weld-Blundell collection (W.-B. 62),

extends the list of pre-diluvian monarchs

to ten,

a figure which has been compared with that of the ten pre-Flood patriarchs mentioned in the Hebrew tradition

(Gen.v.3-end

P).

Ingenious but unconvincing attempts have indeed been made to trace a correspondence

between the actual names given respectively in the Babylonian and Old Testament lists.

The reader may like to compare the lists [As reconstructed by S. Langdon.] for himself:

| Cuneiform | Berosus | Bible | |

|---|---|---|---|

1. |

Alulim |

Alorus |

Adam |

2. |

Alagar |

Alaparos |

Seth |

3. |

Enmenluanna |

Amelon |

Enosh |

4. |

Enmenanna |

Ammenon |

Cam |

5. |

Damuzi |

Daonos |

Mahalalel |

6. |

Ensibzianna |

Amempsinos |

Jared |

7. |

Enmenduranna |

Euedorachus |

Enoch |

8. |

Ubardudu |

Opartes |

Methusaleh |

9. |

Aradgin |

Megalaros |

Lamech |

10. |

Zinsuddu |

Xithuthros |

Noah |

More sensational in some ways than the finding of the Flood tablets was the discovery in 1929 of traces of

the Flood itself.

Excavating almost simultaneously Langdon at Kish and Woolley at Ur penetrated the layer of 3000 BC,

and found beneath it a sudden complete break in the pottery deposits,

together with an unpierced stratum of sand or clay containing remains of aquatic life,

which had clearly been left by a deluge of unparalleled

dimensions and persistence.

[S. Langdon, Excavations at Kish (1929);

C. L. Woolley, Ur of the Chaldees (1929).

Kish, near Babylon, is believed to have been the oldest city in the

world,

dating back to beyond 5000 BC. W.O.P. 413.]

Woolley's account of his discovery at Ur is worth quoting:

'The shafts they were digging went deeper, and suddenly the character of the soil changed.

Instead of the stratified pottery and rubbish,

we were in perfectly clean clay, uniform throughout,

the texture of which showed that it had been laid there by the water.

The workmen declared that we had come to the bottom of everything.

I sent them back to deepen the hole.

The clean clay continued without change until it had attained a thickness of a little over eight feet.

Then, as suddenly as it had begun, it stopped

and we were once more in layers of rubbish full of stone implements and pottery.'The great bed of clay marked, if it did not cause, a break in the continuity of history.

Above it we had the pure Sumerian civilization slowly developing on its own lines:

below it there was a mixed culture.'No ordinary rising of the rivers would leave behind it anything approaching the bulk of this clay bank:

eight feet of clay imply a very great depth of water,

and the flood which caused it must have been of a magnitude unparalleled in local history.

That it was so is further proved by the fact that the clay bank marks a definite break in the continuity of local culture:

a whole civilization which existed before it is lacking above it,

and seems to have been submerged by the waters.'There could be no doubt that the flood was the Flood of Sumerian history and legend,

the Flood on which is based the Story of Noah.'

A Typical 'Tower of Babel.

Recently excavated ziggurat of Ur of the Chaldees,

Built of solid brick, and originally surmounted by a lofty temple.

The low plains of southern Babylonia are to this day dotted with

ruined towers, several of which have been identified at various times with the Tower of Babel.

The Biblical description of the

building of such towers has been verified by archaeology.

They were built of 'brick', which was 'burnt thoroughly'.

There are no

quarries in the district, so 'they had brick for stone', perforce,

and 'slime', that is bitumen, 'they had for mortar'.

They were

composed of solid platforms of brick

[Unlike the pyramids, they concealed no hidden tombs or

treasure-chambers,

though often there were small built-in cavities containing foundation-records.],

rising in terraces, and

ascended by an inclined ramp or stairs to where a temple crowned the summit.

Apart from their religious purpose, these ziggurats,

as they were called, served as rallying-posts for the people, lest they be 'scattered abroad upon the face of the whole earth',

and doubtless often formed the nucleus of a 'city', to which a 'name' would be given, inscribed in cuneiform upon the tower.

Many inscriptions recording the building or repair of such ziggurats have been unearthed. Hammurabi, for instance, tells us that he 'made the summit of the Temple Tower in Uruk high, and amassed provisions for Anu and Ishtar, as the protector of the land, who gathered again the scattered inhabitants of Isin'.

Up to the present century the striking ruins of the Birs Nimrud,

still standing a mass of jagged masonry 150 feet above the plain, were frequently identified with the Tower of Babel, though it

had rivals in the Akerkufor Nimrod's Tower, and in the mound at Hillah which is still called Babil by the Arabs.

Today, however,

it is generally agreed that the 'Tower of Babel' must have been within the walls of Babylon itself, and that its most probable

site is the ruined temple or Etemenanki, whose exact position is now certain.

[B. T. A. Evetts, New

Light on the Bible (1892), has a good account of early Babylonian exploration;

also H. V. Hilprecht, Exploration in Bible

Lands (1903).

See also W.O.P. 897 (by H. R. Hall).]

The Etemenanki is nothing much to look at today compared with

the Akerkuf or Birs Nimrud.

Little remains but the base of a great square tower surrounded by a ditch.

But it was once, we need

not doubt, a noble edifice whose top almost reached to heaven.

It was so high, apparently, that its pinnacle was in fact

constantly toppling,

and there are many records of its repair.

In several of these we find the ominous words 'Its top shall reach

the heavens'.

Nebuchadrezzar, for instance, writes:

I raised the summit of the Tower of stages at Etemenanki

so that its top rivalled the heavens.

George Smith [G. Smith, Chaldaean

Account of Genesis (1880).]

also quotes a remarkable fragment relating to the collapse of such a ziggurat:

The building of this temple offended the gods.

In a night they threw down what had been built.

They scattered them abroad, and made strange their speech.

The progress they impeded.

mdash;a passage which is certainly reminiscent of the Bible story.

top