Chapter II: The Text

HOME | The need for an adequate text of the NT | Modern textual criticism occasioned by the necessity of testing the Textus Receptus | Pedigrees of manuscripts and pedigrees of variant readings | The Byzantine Text and the Vulgate | The versions and the evidence of the Fathers | ... Alexandria | ... Caesarea | An example of the textual critical method ‑ Mk.i.2. | Further examples, from the Parable of the Ten Virgins, raising the historical problem |The need for an adequate text of the New Testament

If the examination of the meaning of the important Greek words which recur again

and again in the New Testament documents raises an acute historical problem, since it points to a particular historical occurrence

in Palestine:

if there can be no understanding of the New Testament apart from the possibility of delineating the significance of

that particular history, at least in its main outlines:

and further, if that history must be reconstructed from the New Testament

documents, since we have no other available sources of information:

it is at once evident that no reconstruction of the history is

possible unless the critical historian has reasonable confidence that the text of the New Testament has not suffered serious

corruption during the fourteen centuries when it was transmitted by scribes.

No serious historical work can be undertaken on the

basis of texts that may be suspected of being radically corrupt.

Top

Modern textual criticism occasioned by the necessity of testing the Textus Receptus

The work of the textual critics during the past two centuries has given the

historian precisely that general confidence which he requires, and has provided him with at least an adequate text of the New

Testament in Greek.

This is a very remarkable achievement, in which English scholarship has played a major part.

Since, however,

textual criticism leaves a number of problems still unsolved, it is essential to summarize the main results of this long and

patient investigation of the manuscripts in order to make clear what conclusions have, in fact, emerged.

In theory, the aim of

textual criticism has been to lay bare what the authors of the New Testament documents actually wrote.

In practice, the aim has

been, first to test the value of the printed text upon which all the older commentators worked, known as the Textus Receptus

‑ the text 'received by all', as the printer of the 1633 EIzevir edition boldly announced in his preface ‑ and,

secondly, to trace the pedigrees of variant readings, which appear scattered about in the extant Greek, Latin, Syriac, Coptic,

Armenian, Georgian, Gothic and Abyssinian manuscripts of the New Testament, and which were known to the early fathers of the

church.

We now know exactly upon what the Textus Receptus was based.

It was based upon a twelfth‑century Greek manuscript that Erasmus sent to be printed at Froben's press in Basle in 1515.

In

the margin of this manuscript Erasmus substituted in his own hand a few variant readings from another twelfth‑century

manuscript also accessible to him in Basle.

Since, however, neither of these manuscripts contained the book of the Revelation of

St. John, Erasmus procured another, which seems to have been formerly at Basle but is now preserved in the Oettlingen‑Wallerstein

Library at Mayhingen, a village not far from Ulm, and which contains only the text of the Revelation and a commentary upon it.

Erasmus was thus able to fill up what was lacking in his other Basle manuscripts.

His procedure is illustrated by the fact that,

since the Mayhingen manuscript lacks the last six verses, Erasmus, having no other manuscript of the book at hand, himself

translated them into Greek from the Latin.

The Greek text published by Froben in March 1516, side by side with the new translation into Latin, which Erasmus had made, was

therefore issued with all the prestige of his name.

But it was, in fact, substantially the text of a single manuscript now known by the Arabic numeral 2.

The Erasmus Greek Testament was, however, to gain further prestige.

The famous Greek Testament issued by Robert Stephanus from the Royal Press at Paris in 1550 was based upon it.

Stephanus had, it is true, introduced quite a large number of corrections from the magnificent Greek text printed at Alcala under

the patronage of Cardinal Ximenes in 1520, usually known as the Complutensian (from the Latin place‑name of Alcala), and in

addition he introduced in the interior margins of the text a number of variant readings from the Complutensian and also from

fifteen other manuscripts including codex Bezae and codex Regius, which had been collated for him by his son Henry.

Stephanus had, it is true, introduced quite a large number of corrections from the magnificent Greek text printed at Alcala under

the patronage of Cardinal Ximenes in 1520, usually known as the Complutensian (from the Latin place‑name of Alcala), and in

addition he introduced in the interior margins of the text a number of variant readings from the Complutensian and also from

fifteen other manuscripts including codex Bezae and codex Regius, which had been collated for him by his son Henry.

Finally

EIzevir reprinted the first edition of Theodore Beza's text, which did not differ essentially from the text of Robert Stephanus,

and this was the Textus Receptus upon which all work upon the New Testament in Greek was principally grounded until quite modern

times.

Thus we may almost say that a single twelfth‑century manuscript provided the text upon which our English post‑Reformation

knowledge of the primitive church rested until Westcott and Hort published their Greek Testament in 1881.

The discovery of the manuscript authority behind the printed Textus Receptus, however, tells us nothing, unless a judgement be

possible concerning the value of the readings contained in manuscript 2.

But it is impossible to test the readings contained in this manuscript unless the critic can trace, not only their pedigrees but

also the pedigrees of competing variant readings that are found in other manuscripts.

It is evident that if the birth of a

particular variant reading can be detected in the course of the transmission of the text, that reading must be removed from the

authentic text, since its origin will have been exposed.

It is evident also that if the purpose of textual criticism be to track

the pedigrees of readings, this pedigree hunting is possible only if the pedigrees of the manuscripts themselves can be

discovered, and their provenance disclosed.

Textual criticism cannot move safely without the help of palaeography.

It will be seen

then that we are in the presence of a very delicate and absorbing science.

Yet, in spite of its difficulty, quite definite

conclusions have been reached.

Top

Pedigrees of manuscripts and pedigrees of variant readings

Of the hundreds of manuscripts of the New Testament in Greek at present in

existence,

it would be hard to find two in all respects alike.

Variations in spelling,

variations in order,

variations in actual words and even in whole verses,

make each more or less distinct.

This lack of identity springs from the very nature of transcription by hand.

No copyist, however lavish of his care or skilful in his craft, can avoid occasional error in the spelling and ordering of words:

no subsequent copyist noticing a consequent nonsense,

is likely to resist giving it meaning by correction.

And so, not errors only, but erroneous reconstructions as well, are incorporated in the text and handed on in every fresh

transcription.

The original is left further and further behind;

contradictions between manuscripts of different traditions multiply,

and presently attempts are made to reconcile them.

The result is chaos.

In the midst of this chaos, the textual critic sets to work.

Until the publication of the Chester Beatty Biblical Papyri in 1933 there was no codex known to scholars that

was older than the fourth century.

Until the publication of the Chester Beatty Biblical Papyri in 1933 there was no codex known to scholars that

was older than the fourth century.

The Chester Beatty fragments are considerable fragments of papyrus codices and are dated with some confidence by Sir Frederic

Kenyon in the third century.

There do, of course, exist tiny papyrus fragments of an earlier date.

Even so, no text has been preserved that is not the result of several transcriptions.

Although a certain number may be singled out as less corrupt than others, when these disagree none has established sufficient

confidence in itself to justify its unquestioned adoption.

Careful comparison of the manuscripts has shown that many of them agree in their choice of a certain

proportion of the disputed readings.

These may therefore be grouped together.

This is the starting point of textual criticism.

For, in the first place, it makes possible rough pedigrees of manuscripts.

If all the copies of the New Testament ever made were extant today, it would be simple to discover how they stood in relation to

each other and to the original autographs.

For each copyist, though he corrected perhaps a certain number of more obvious slips,

must have handed on many of the errors of the transcription before him.

And so, as scribe after scribe copied the text, there came

into being distinct traditions, recognizable by the peculiar colour of their variant readings.

Therefore, if all the manuscripts

of a group which generally agree preserve a particular reading not found elsewhere, it is evident, either that the reading was

original and that all other transcriptions are in that respect erroneous;

or that the copyist of some particular manuscript, from

which the whole group descended, introduced this variant into the text.

Conversely, if two or three manuscripts of such a group

have readings unknown to the earlier members of the group, it will be probable that the responsible error was made in some

manuscript later than these earlier members.

In this way, some variant readings are shown to be late and irrelevant, others to be

early and quite possibly original.

But the chief purpose of trying to ascertain the pedigrees of manuscripts and their place in the traditions

of the text is to discover distinct textual traditions.

For, where it can be proved that the agreements of two manuscripts are due

to a common ancestor, those agreements are only guaranteed as far back as the common ancestor.

But where manuscripts that

represent an independent transmission of the text agree in a whole series of readings, this agreement warrants the assumption that

these readings were current in very early days, precisely because their birth eludes detection.

The process of tracking the pedigrees of readings reveals the existence in the fourth and fifth centuries of

distinct lines of textual tradition.

As soon as the books of the New Testament began to be valued,

copies were made and distributed among churches.

At first, no doubt, the autographs were copied;

then the copies themselves.

During the first five centuries, the life of the church revolved round great cities such as Rome, Lyons, and Carthage in the west,

Antioch, Ephesus, Caesarea and Alexandria in the Middle East, and Edessa on the eastern border of the Roman Empire.

These centres must presumably have possessed important manuscripts of the New Testament, and these manuscripts may well have

exerted an influence upon the books used in surrounding districts, since, whenever new copies were needed, recourse would be had

to the nearest great city.

Top

The Byzantine Text and the Vulgate

With the reign of Constantine and the peace of the church there began a new era,

marked by the emergence of the growing prestige of Rome and of Constantinople.

Not only was it necessary to replace the scriptures

destroyed during the great persecutions, but also there was far closer intercourse between the various churches, which produced

both a mixing of the texts and important authorized revisions of the whole New Testament.

The aim of these revisions was partly to

introduce a generally accepted text, and partly to remove those unliterary features of the earlier manuscripts, which were not

fitted to the new respectability of the church, and shocked the delicate sensibilities of men and women accustomed to the

classical literature of Greece and Rome.

It was during this period that a whole series of readings appeared of which the early

fathers had known nothing:

during this period also the text of the New Testament became more or less fixed both in Greek and in

Latin.

The most epoch‑making revision seems to have been made at Antioch at the beginning of the fourth century by a certain

Lucian.

In making his revision he was not only concerned to produce an elegant, easily running text, but amalgamated or conflated

variant readings already in existence.

It is probable that during the next four hundred years his revision of the text lay behind

the gradual standardization of the official text of Byzantium, the political centre of the Eastern Empire.

The Byzantine text became the authorized version of the Greek Church.

Nearly all extant Greek manuscripts are therefore either founded upon it, or more or less corrected into conformity with it; and,

since MS 2 represents this text, it formed the basis of the Textus Receptus.

What happened in the cast happened also in the west.

Damasus, bishop of Rome during the second half of the fourth century, instructed Jerome to undertake a revision of the old Latin

versions.

Jerome produced his revision, and this revision, known as the Vulgate, gradually submerged the old Latin versions, took

control of the transmission of the Latin text, and became the authorized version of the western church.

Jerome produced his revision, and this revision, known as the Vulgate, gradually submerged the old Latin versions, took

control of the transmission of the Latin text, and became the authorized version of the western church.

The effect of these authoritative revisions was that manuscripts representing the state of the text before

these revisions fell into disuse, and, with certain significant exceptions, disappeared.

Nearly all existing Greek and Latin manuscripts have been influenced by these revisions.

Yet, even so, because the older

traditions were firmly rooted in many parts of the church, and because it was easier to correct the obvious variants than to

obtain fresh copies, many older readings have been preserved.

It is therefore possible to distinguish in the first place between

revised and unrevised readings.

Where manuscripts depart from the text of the revision by which they have been influenced, and

their variants are not obviously later corruptions, the variant may be said to be unrevised.

These unrevised readings, unless they

can be explained in some way or other as obvious corruptions, have to be taken seriously, since it is impossible to detect their

birth.

It is now possible to define precisely the critical procedure in handling variant readings.

Where a variant

came into being with one of the great revisions and was unknown before that revision, it must be put on one side, for its origin

has been discovered.

The whole interest now centres in variant readings known to have existed before the great revisions.

Here a

canon of criticism emerges.

If it be clear that a variant reading was current in more than one of the textual traditions of the

second and third centuries, its pedigree escapes detection, and from the point of view of pure textual criticism it cannot be

removed.

The textual critic can only say that it was current in the second century.

Top

The versions and the evidence of the Fathers

The versions and the evidence of the Fathers

The detection of variant readings which existed before the great revisions

is assisted by a study of the Egyptian and Syriac versions, and of those existing Latin manuscripts which are wholly or in part

uninfluenced by the Vulgate.

The New Testament was translated from Greek into Coptic, Latin and Syriac, before the fourth century.

Thus the Egyptian versions reflect the form of the older text of Alexandria from which they were probably made.

The old Latin

manuscripts represent versions made from the Greek before the Byzantine revision.

The Syriac versions, and very particularly the

two surviving manuscripts of the old Syriac version, also represent the Greek text before, or apart from, the Byzantine revision.

The text used by the early fathers is of course all-important here.

Top

... Alexandria

... Alexandria

Hitherto, readings current behind the two great revisions have been called

un-revised readings, but there is evidence that a revision of the Greek text had in fact already been undertaken in Alexandria at

the end of the second century or at the beginning of the third.

Alexandrian scholars had long been familiar with the difficulties

of manuscript tradition and were skilled textual critics, for similar problems had arisen in the transcription of the classical

authors.

Alexandria, indeed, was of all centres of early Christianity the place where a skilled judgement upon variant readings in

the New Testament manuscripts might be expected, and this expectation is in fact borne out by the survival of a series of

manuscripts, some of them with a clear Egyptian provenance.

The most important manuscripts in this connexion are codex Vaticanus, codex Sinaiticus, the Paris palimpsest (C), codex Regius,

minuscule 33, manuscripts of the Egyptian versions, especially the Sahidic version, and of the Ethiopic (Abyssinian) version, and

also the texts used by Origen while he lived at Alexandria.

The most important manuscripts in this connexion are codex Vaticanus, codex Sinaiticus, the Paris palimpsest (C), codex Regius,

minuscule 33, manuscripts of the Egyptian versions, especially the Sahidic version, and of the Ethiopic (Abyssinian) version, and

also the texts used by Origen while he lived at Alexandria.

These manuscripts contain a large number of readings not found elsewhere.

It is important to remember, however, that if these readings are the result of a revision, they rest upon a scholarly judgement

and there is no evidence whatever that this judgement was based upon knowledge of the autographs.

Moreover, the Alexandrian scholars were possessed of a nice sense for correct literary Greek, and there is every reason to suppose

that they tended to smooth out the roughness of the earlier tradition and to substitute, so far as this was possible, a greater

literary elegance.

Yet, at the same time, they undoubtedly rid the text of obvious errors and preserved many venerable readings, which might

otherwise have been lost.

Top

... Caesarea

A recent analysis of the readings contained in a number of manuscripts has drawn

attention to another centre of distribution of readings, if not, indeed, of another revision of the text.

Caesarea during the

fourth century was a very important centre of Christian erudition.

It was there that Eusebius wrote his history of the church, a

work which could not have been composed had Eusebius not had a library behind him.

And that there was a library there we know

because he tells us that Pamphilus, the admirer of Origen, added to the library of Caesarea the works of Origen and of other

ecclesiastical writers (Eusebius, Ecclesiastical History VI, 32).

Pamphilus founded at Caesarea a school of sacred learning and

spent much time in transcribing and correcting manuscripts of the scriptures and especially of the Septuagint as it had been

edited in the Hexapla of Origen (see Lawlor and Oulton, Eusebius Ecclesiastical History, Vol. II, pp. 331 f.).

Codex Koridethi, Mark v.31‑xvi.8 in the Washington codex, minuscules 28, 43, 565, 700, and

family 1 and family 13, and also the most ancient surviving manuscripts of the old Georgian version, although nearly all

influenced by the Byzantine text, nevertheless contain a series of remarkable variant readings, readings which seem, moreover, to

have been known to Origen when he was at Caesarea.

It is therefore not unnatural to see in their agreements a common influence.

This does not, of course, mean that these readings originated in Caesarea;

indeed, they are at times supported by the Chester

Beatty papyrus codex and were therefore, as Kenyon has pointed out, already current in Egypt at an earlier period.

They may well, however, have circulated from Caesarea.

It is possible, then, to distinguish, behind the great Byzantine and Vulgate revisions, several distinct

traditions of the text.

This is of great importance.

For it means that the agreement of any two of these fairly independent

traditions, in any variant reading, places it beyond the judgement of the textual critic, and that even a reading found in one of

them only cannot safely be dismissed.

Nevertheless, it is difficult to give a pre-eminent authority to any of these traditions, or

to agreements between any particular two of them.

None is infallible, and each on occasion seems to preserve the right reading by

itself.

When all is said and done, each reading has to be examined on its individual merits.

Therefore textual criticism is at

this point merged in the general interpretation of the New Testament, and ceases to be a distinct branch of New Testament study.

Top

An example of the textual critical method ‑ Mk.i.2.

The great labour spent during the past two centuries in collating

manuscripts, and in tracing their pedigrees in order to track the pedigrees of variant readings, has enabled scholars to arrive at

confident conclusions upon very large number of variant readings.

For example, a conclusion seems to be reached by pure textual

critical methods on the variant reading to Mark wrote either: 'as has been written in the prophets,' or 'as has been written in Isaiah the prophet.' [Mark i.2.]

He follows up his statement with two Old Testament quotations, one from the book of Malachi [Mal.iii.1.], the other from Isaiah [Is.xl.3.].

The question is whether,

knowing that he was quoting from the prophets, he said so, and subsequently a scribe blundered, or whether the blunder was his.

External evidence ‑

The manuscript evidence is as follows:

the reading in the prophets is supported by the vast majority of the Greek manuscripts and

was therefore the reading adopted in the Byzantine text.

Did the Byzantine text initiate this reading, or merely establish it?

It

is also the reading in the Washington codex, in minuscule 28, in family 13, in the text of the Harklean Syriac version, in one

manuscript of the Egyptian Bohairic version, in the Armenian and Ethiopic versions, and is known in one manuscript of the old

Latin version.

It

is also the reading in the Washington codex, in minuscule 28, in family 13, in the text of the Harklean Syriac version, in one

manuscript of the Egyptian Bohairic version, in the Armenian and Ethiopic versions, and is known in one manuscript of the old

Latin version.

Moreover the passage is also thus quoted once in the Latin translation of Irenaeus.

Were it not for these two Latin

readings and the Ethiopic version it would seem that at no point does the evidence necessarily go behind the Byzantine text.

The

evidence is therefore weak, but it is not yet possible to say with certainty that the Byzantine text did more than establish an

already existing reading.

The manuscript evidence for the reading in Isaiah the prophet is as follows:

it is supported by codex Vaticanus, codex Alexandrinus, codex Bezae, codex Regius, codex Koridethi, by nine Greek minuscules

including 33, 565, 700, and by family 1.

The whole Latin manuscript evidence, old Latin and Vulgate, with the exceptions already mentioned, confirms this reading.

So also do the Syriac, Coptic, and Georgian versions, and four manuscripts of the Armenian version.

In addition it is supported by three out of the four occasions upon which Irenaeus refers to the passage, by Origen, Epiphanius,

Basil of Caesarea, Jerome and Augustine.

Owing to the wide geographical distribution of this evidence it would almost seem that this must have been the original reading.

Since, however, there may still be some uncertainty the internal evidence must also be taken into account.

Internal evidence ‑

Let it be supposed that in the prophets was the original reading.

Can the emergence of the reading in Isaiah the prophet be explained, either by carelessness in transcription or by a conscious

alteration?

There would seem to be no possible explanation of this alteration on either ground.

Let it be supposed, on the other hand, that Mark wrote in Isaiah the prophet.

The correction to in the prophets is almost demanded, not by carelessness of transcription, but in order to avoid ascribing the

quotation from Malachi to the prophet Isaiah.

The conclusion is inevitable.

Mark made the blunder, and it was finally removed.

But there is more than this.

If it be assumed that Mark did write in Isaiah the prophet the procedure of Matthew and Luke, who delete the quotation from

Malachi while preserving the name Isaiah, is intelligible.

Thus they remedy Mark's blunder by very drastic methods.

A comparison of the three gospels therefore shows Mark's eagerness to open his gospel with impressive Old Testament quotations.

But it also shows the accurate knowledge of the Old Testament possessed by both his editors.

Top

Further examples, from the Parable of the Ten Virgins, raising the historical problem

Textual criticism has shown that there was no serious corruption of the

text of the New Testament between the fourth century and the invention of printing, and that even the Textus Receptus would not

lead the theologian or the historian far astray.

None the less, of the large number of interesting variant readings already

current during the second and third centuries, the original reading cannot be determined by textual criticism alone.

The very

subtle problems that they present can be handled, but only by the New Testament historian who is beginning to reach conclusions in

other branches of New Testament critical study.

A discussion of the Matthaean parable of the Ten Virgins [Mt.xxv.1‑13.],

which contains two interesting and important variant readings, illustrates this merging of textual criticism in the general field

of New Testament exegesis.

In the first verse most manuscripts read, 'Then shall the kingdom of heaven be likened unto ten virgins,

which took their lamps and went forth to meet the bridegroom.'

But several manuscripts read 'went forth to meet the bridegroom and the bride.'

The textual evidence is as follows:

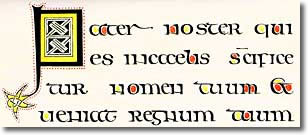

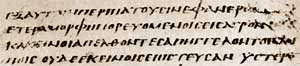

![]() The longer reading, containing the words and the bride, is found in the Vulgate and in the old Latin

versions, in the Greek of the codex Bezae, in one of the manuscripts representing the old Syriac version, in some later Syriac

manuscripts and in the Armenian versions.

The longer reading, containing the words and the bride, is found in the Vulgate and in the old Latin

versions, in the Greek of the codex Bezae, in one of the manuscripts representing the old Syriac version, in some later Syriac

manuscripts and in the Armenian versions.

It is found also in certain interesting Greek manuscripts headed by codices Monacensis

and Koridethi.

The vast majority of the Greek manuscripts and of the other versions have the shorter reading.

Everything, then, points to the fact that both readings were current in the second century.

That is to say,

the birth of neither of these readings can be detected in the transmission of the text.

Having established this, textual criticism

can do no more.

The decision as to which reading is to be adopted must be handed over to the historian.

The longer reading is

easily intelligible.

It rivets the parable to the ancient custom of the bridegroom going forth to meet the bride, and bringing her

back to his own house.

But on this basis it is possible to argue in diametrically opposite fashions.

On the one hand, it may be

supposed that the sight of an actual wedding gave form to the parable, and that Jesus simply took the incidents as they appeared,

and gave them further meaning.

By this reasoning, the procession of the bride and bridegroom, and the group of virgins at the door

of the house, owe their existence to wedding custom.

It is true that the bride plays no part in the story.

But why should she?

Jesus is telling a story to illustrate a spiritual truth;

the details of the story have no further special significance.

On the

other hand, if the shorter reading be adopted, the parable is an eschatological parable, and the isolation of the bridegroom

emphasizes the final coming of the messiah at the end.

The absence of the bride is then essential, and an illustration from common

custom is manipulated in order to secure the eschatological significance.

We are then faced by a clear alternative.

Either the

bride's presence is original, and omission of her is due to the pressure of the eschatology and to a desire to trim the original

text so that it may more clearly display the eschatological significance and emphasize Jesus as the coming judge;

or the isolation

of the bridegroom is original, and the bride is added in order to bring the parable into harmony with known wedding customs, and

to make the story more vivid to those readers who were familiar with such scenes.

It is clear that we are here in the presence of an historical problem of the first magnitude.

It concerns the nature of the teaching of Jesus, or at least the emphasis in the Matthaean record of that teaching.

Did the

evangelist preserve hints that Jesus taught moral and spiritual truths by means of simple stories reflecting common occurrences in

the experience of his hearers;

or did he preserve in his record evidence that common occurrences were in the parabolic teaching of

Jesus twisted out of their context in order to express the gospel of God which in its essence could be interpreted only by the use

of eschatological language and imagery?

In other words, did the manipulation of wedding custom take place in the mind of Jesus or

in the course of Christian interpretation of his teaching?

The same parable contains another variant reading of subtle significance.

At the crucial moment in the story the foolish virgins beg some oil from their prudent companions.

How, in fact, do the wise virgins answer this request?

According to one reading, which is supported by the uncial codices, Sinaiticus, Regius, Dublinensis, and by a few minuscules

including the Paris manuscript numbered 33, they refuse the request more or less politely: 'Perhaps there will not be enough for us and you.'

According to another reading, which is supported by the vast majority of the Greek manuscripts headed by

codex Vaticanus and codex Bezae, they answer, with almost incredible brutality: 'Never! There will certainly not be enough for us and

you.'

According to the first reading, there is no particular emphasis upon the answer of the wise virgins, and the

reader moves on undisturbed.

If the second reading be adopted, the whole point of the parable lies in the roughness of the answer.

The oil that enables the wise to enter with the bridegroom is un-transferable oil;

there can be no loan or gift of that which

secures salvation.

Here is a terrible sternness;

here is no easy humanitarianism, no brotherly or sisterly tenderness;

here, when

ultimate salvation is at stake, there emerges what to the modern reader seems arbitrary cruelty.

Again the historical problem

arises in the midst of a delicate problem in textual criticism.

On which side did the Jesus of history stand?

Did his parables follow the natural course of a story, or was the story broken by a terrible moral earnestness challenging the

hearers to a decision upon which hung an ultimate issue?

Was he a kind philanthropist, whose teaching has been complicated by the intrusion of a harsh eschatological supernaturalism, or

does the grim eschatology belong to the original history, and is the tenderness precisely the intrusion?

This is the historical problem raised in one form or another by the whole of the New Testament material, and it is raised by the

existence of variant readings between which the textual critic cannot decide.

The decision is therefore handed over to the

historian.

The issue that underlies so many of the variant readings is just the same issue as was found to underlie the problem of

the meaning of New Testament words.

Once again the problem is the Jesus of history and the origin of the church.

Top

NOTE

An admirable introduction to the textual criticism of the New Testament has been written by Leon Vaganay,

Introduction to the Textual Criticism of the New Testament, London 1937, a translation of one of the volumes of the Bibliotheque

Catholique des Sciences Religieuses.

Dr. Souter added to his Greek text of the New Testament, published at the Clarendon Press, a

selection of variant readings.

However, for a compendium of variant readings the eighth edition of Tischendorf's text has hitherto

been indispensable.

Since this edition was published between 1869 and 1872, it of course contained no reference to manuscripts

discovered since that time, nor to the groups of minuscules such as family 1 and family 13, which have been seen to be so

important.

The work of Tischendorf is now being brought up to date.

The publication of Westcott and Hort's text with a complete

critical apparatus has been undertaken by the Clarendon Press, and the first two volumes, the Gospel of Mark, and the Gospel of

Matthew, both edited by S. C. E. Legg, were published in 1935 and 1940 respectively, C. R. Gregory's Prolegomena, printed as

Vol. III of the eighth edition of Tischendorf's Novum Testamentum Graece from 1884 to 1894, is still the most complete and

elaborate and indispensable description of the material relevant to textual criticism.

It was separately published in German,

corrected and expanded, under the title Textkritik des Neuen Testamentes, Leipzig, 1900‑1909.

The relevant evidence for the

textual criticism of the Acts of the Apostles is accessible in The Text of Acts by J. H. Ropes, Vol. III of The Beginnings of

Christianity, ed. by Foakes Jackson and Kirsopp, Lake, London, 1926.

Top