CHAPTER IV: FORMATION OF THE DISCIPLES AND MINISTRY, CHIEFLY OUTSIDE GALILEE

3. AT THE FEAST OF TABERNACLES

HOME | Contents | PART II | PART III: About the Feast of Tabernacles | 137.Jesus' refusal to manifest Himself at Jerusalem | 138.Jesus goes up to Jerusalem | 139-141.First conversations and impressions during the feast | 142-3.Teaching on the first day of the feast; disagreement even among the Pharisees | 144.The woman taken in adultery | 145.The light gives testimony of itself, and that testimony is confirmed by the Father | 146.The danger of refusing to acknowledge God's envoy | 147.In Jesus is the salvation announced to Abraham | 148.The man born blind | 149-150.Jesus the door of the sheepfold and the Good Shepherd.

The third of the feasts on which the Israelites were commanded to go on pilgrimage

to Jerusalem was 'the feast of Tents,' or as we say 'of Tabernacles.'

These

tents were not like the tents of the Bedouin, 'houses of hair' as they call

them because made of camel hair cloth;

they were huts of boughs.

In every

vineyard there was a tower of uncemented stone on the flat roof of which it

was a simple thing to erect one of these huts.

It was there that the owner

of the vineyard slept at the time when the grapes were ripening in order to

protect them against jackals, and against human thieves too.

When the grape-harvest

was over a few days were spent there in rejoicings.

Just as the feast of the

first fruits had grown into a commemoration of the giving of the Law on Sinai,

so also the feast of Tents had been consecrated to the memory of the exodus

from Egypt;

[Exodus xxiii.16:

'Thou shalt observe the feast of the harvest of the

first fruits of thy work (later become the feast of

the Law) ...

(and) the feast also in the end of the year when thou

hast gathered in all thy corn out of the field.'

Cf. Leviticus xxiii, 43:

'that your posterity may know that I made the children

of Israel to dwell in tabernacles

when I brought them out of the land of Egypt.']

but the latter identification was of much earlier date than

the former.

It was in this way that God educated His people,

transforming

the rejoicings of the grape-harvest,

which were not infrequently the occasion

of licentiousness,

by providing them with another and higher motive.

Thus

gratitude to God for the natural blessings of the earth was by this commemoration

directed towards the great supernatural favours which Israel had received.

That divine process finds its completion in the Christian religion which

has made all feasts serve to recall some mystery of our salvation.

In consequence of its origin the feast of Tabernacles was not considered to

be so great as the Pasch;

it did not call up such sacred memories of the past,

pledges of a still holier time to come.

But, on the other hand, the feast of

Tabernacles was a more joyful occasion, as vintage feasts are all over the

world.

Apart from the special sacrifices that were common to all festivals,

the special rite of this feast

was that worshippers carried during the ceremony

a sort of bouquet made of branches and fruit.

Originally the Law had prescribed

a bunch of palm and willow branches.

By the time of Josephus, almost contemporary

with Jesus, tradition had interpreted this as meaning branches of myrtle, willow,

and palm, along with Persian apples, that is to say lemons.

At the time of

the celebration,

the end of September or beginning of October,

the agricultural

year was at an end

and the land was parched by the sun.

[The agricultural year regulated the civil year.

The new year began and still begins on the first day of Tishri;

the feast of Tabernacles began on the 15th.]

The thoughts of

all were now turned towards the next sowing,

and this would depend on the gift

of rain.

Doubtless it was to symbolize the hoped-for rain that water was brought

from Siloe in a precious vessel during the feast and poured upon the altar.

It expressed their desire that the water from the spring might thus go up to

heaven and fall upon Israel afresh.

The rite was performed on each of the seven

days of the feast, perhaps on the eighth day also, though this had the character

of a distinct feast.

We do not learn explicitly from the Jewish writings that

the pilgrims were welcomed at Jerusalem with great pomp and ceremony, but it

is probable that they were so received.

Doubtless also they brought with them

their bunches of boughs and fruit so as not to pay the great price that would

be demanded at Jerusalem.

Entering thus into the city with a company of Galilaeans

was for Jesus a kind of foretaste of the modest triumph He was to enjoy in

a similar manner at the following Pasch.

top

The refusal of Jesus to manifest Himself at Jerusalem (137).

We left Jesus after His farewell to Galilee.

He had traversed that country

almost secretly in order that He might not be disturbed in the attention He

was devoting to His disciples.

We here pick up again the thread of the fourth

gospel,

where too we find Jesus in His own country,

for He had not returned

to Judaea since the last Pentecost.

On that occasion, after He had cured the

paralytic on the Sabbath day,

the Jews had made up their minds to do Him to

death.

Four months had passed and it was time to go up to the Holy City again

for the celebration of the feast of Tabernacles.

The brethren of Jesus, His

near relations that is to say, knew of His presence in their neighbourhood

and were becoming impatient at His evasions of public notice.

They had not

a belief in Him like that of the Apostles;

[None of them, that is with the exception of James, the

son of Alphaeus;

if this James, indeed, is 'the brother of the Lord,' as we think him to be, and

the son of either a sister or a cousin of the Blessed Virgin.

Whether Alphaeus be the same as Cleophas or not cannot be said with certainty.]

but if their kinsman was thinking

of playing a great part, and if, as seemed possible,

His undeniable miracles

gave Him some chance of success,

why all this evasion?

Let Him make the attempt.

As far as Galilee was concerned the cause seemed hopeless;

but Jesus had followers

at Jerusalem;

that was the right place to manifest Himself to the world,

a place where He

would find the elite of Israel.

A triumphal entry into the Holy City surrounded

by a group of resolute Galilaeans shouting joyful Hosannas, what an opportunity

that would be for Him to set up as a Liberator!

It almost seems as though

His brethren offered to join His supporters.

But Jesus prefers to let them go up without Him:

'Go you up to the feast,

but as for Me,

I go not up to this feast

because My time is not yet accomplished';

the time of which He speaks is the time appointed by God.

There is no question

of the evangelist's wishing to accuse his Master of dissimulation;

he simply

means that Jesus reserved His liberty to do as He liked.

Though it is forbidden

to lie even to one that asks indiscreet questions, yet there is no obligation

of revealing our intentions to such a one when there is need to keep them secret.

And secrecy was precisely what Jesus required,

that is to say, He wished to

arrive in Jerusalem quietly.

[The meaning is therefore: 'I go not up yet,' as very many

MSS. have it.]

It was necessary for Him to take this precaution

because the Jews were waiting for Him,

and among the crowd people were discussing

Him in whispers, some for, others against Him,

no one daring to commit himself

too openly until the authorities had declared their mind.

top

Jesus goes up to Jerusalem (138).

Jesus therefore took the road to Jerusalem accompanied by a few disciples

only.

He was leaving Galilee for the last time.

St. Luke has laid emphasis

on the decisive character of this moment,

this journey which was to end in

death after the lapse of a few months.

From now on that is the prospect which

dominates the whole situation.

The shortest route to Jerusalem was through the land of the Samaritans and

it was in Jesus' mind to ask hospitality of them.

But at the season of the

great pilgrimages feelings were more than usually excited.

His little band

was going in the direction of Jerusalem evidently with the intention of carrying

out the rites which it was forbidden to celebrate in any other place;

that

in itself was an insult to the claims of Mount Garizim,

and the Samaritans

refused to receive Jesus and His followers.

James and John, the Sons of Thunder [See above, p. 279.],

found it impossible on this occasion to put a charitable construction on such

a refusal;

people who scorned the sacred law of hospitality could only be

regarded

as open enemies.

Confident in their ability to imitate the example of Elias [4

Kings (2.Kgs)i.10-12.],

if only their Master would allow it, they appeal to Him:

'Lord, wilt Thou that we command fire to come down from heaven and consume them?'

But He

turned and rebuked them, patiently content to go on and look for some other

place of shelter.

[The primitive text of St. Luke said no more than this,

that He rebuked them;

but certain MSS. have added the words:

'And He said to them: You know not of what spirit you

are.

The Son of Man came not to destroy men's If souls but to save them.'

This addition may be derived from Marcion who tried to show the opposition that

existed, in his opinion, between the New and the Old Testaments.

He would be right in seeing an opposition of some sort here,

for the spirit of the New Testament is different in so far as Jesus has come

to save mankind.

And indeed the Church has never seen anything objectionable in this gloss, for

the words appear in the Vulgate to this day.]

top

First conversations and impressions during the feast (139-141).

First conversations and impressions during the feast (139-141).

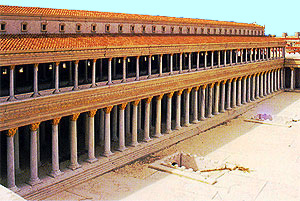

When they arrived in Jerusalem the feast had already begun;

it was already

the middle of the week dedicated to that feast.

Jesus went into the Temple.

After the ceremonies were over it was the custom of the Jews to stay talking

in the great enclosure surrounding the altar and the Holy Place.

There the

rabbis taught, and Jesus followed their example.

By this He caused some surprise,

for people held that He had not attended the rabbinical schools long enough

to acquire authority in them,

to have His opinions quoted with the conventional

formula:

Rabbi so-and-so has said.

This was the honour chiefly coveted by

those who devoted themselves day and night to the study of the Law.

These Jewish

masters put themselves forward merely as repeating the teaching handed down

by tradition;

but, despite this affectation of modesty,

they not infrequently

yielded to the temptation of making some new solution-their own,

namely-prevail

by dint of subtlety.

These solutions had necessarily to be derived from the

Law,

but they were sometimes drawn at the expense of legitimate exegesis,

and

not without doing injury to the authority acquired by other teachers.

But Jesus,

far from making any claim to originality in His doctrine and to the honour

which might accrue to Him on that account, declares that His doctrine is not

His own;

it comes from the One who

sent Him, and to Him all the glory should be attributed.

By thus renouncing

all self-interest.

He left no occasion for anyone to suspect Him of perverting

the truth out of vainglory.

By the One who has sent Him He means God.

But how were they to be sure of

that?

That was the whole point at issue between His adversaries and Himself.

First, He makes appeal to the testimony of an upright conscience.

A will that

cleaves to God is of more use for judging of divine things than is the search

for light by means of study.

In saying this

Jesus lays down one of the great

principles of mystical theology,

that God is known by means of the resemblance

of the knower to the divine object of His knowledge.

A simple and uneducated

woman, if she is good,

has a truer sense of moral goodness than a theologian

who is a bad man.

And this is precisely the case with the Jews who are hostile

to Jesus.

They have the Law of Moses always on their lips,

but they do not

practise it according to its spirit;

that is why they fail to see that Jesus

interprets the Law in the spirit of Him who gave it.

Most certainly no one

ought to claim the right to act contrary to the positive law of God on the

ground that he has received private mystical inspirations.

But in the matter

with which He is reproached, namely the cure of a man on the Sabbath,

Jesus

shows that there was no real transgression of the positive law of God.

Was

not the law of the Sabbath set on one side in order to carry out the rite of

circumcision on newly-born children?

That law then ought not to be made an

obstacle to restoring health.

Indeed did it not stand aside of itself when

there was a question of the law of charity?

Here Jesus was alluding to the cure of the paralytic at the pool of Bezatha

during the last feast of Pentecost, and recalling the fact that the Jews had

then resolved to put Him to death.

Some of the crowd, perhaps people from a

distance, thought that He was suffering from persecution mania and said:

'Thou art possessed by the devil.

Who seeketh to kill Thee?'

[John vii.20.]

Others, however,

living at Jerusalem [John vii.25.], were better

acquainted with the ill-feeling entertained for Jesus by their leaders, and

this made them all the more surprised that they allowed Him to speak so freely.

Was it possible that their leaders had

changed their minds and were now disposed to acknowledge Him as the Messiah?

Surely not, for the Messiah was to appear without anyone's knowing whence He

came, in some miraculous fashion;

and it was only too well known where Jesus

came from.

True, He proceeded to say;

you know Me and you know whence I have

come.

But that is not the thing of importance.

My earthly origin does not prevent

My having come from somewhere higher than this earth,

sent by Him who has the

right to send;

and even if you do not know who He is,

nevertheless I know

Him -

I who am with Him and who have been sent by Him.

Thus in His forbearance

Jesus solved the difficulty at which these thoughtless people had stumbled.

They reckoned on some extraordinary origin for the Messiah;

His was more divine

than they think, though it is not inconsistent with those earthly relationships

of which they are well aware.

His extraordinary origin is pre-existence with

God, who has sent Him and with whom He dwells.

At this declaration some of

them were violently shocked and wished to lay hands on Him;

but others said:

'Why not believe Him,

seeing that He has confirmed what He

says by miracles?

Will the Messiah furnish more splendid proofs than those

when He comes?'

And they believed in Him.

The Pharisees were alarmed

and sought out the chief priests

to whom was reserved

the authority to employ the police in the Temple.

Officers were charged to

arrest Jesus formally;

but He read their intentions and forewarned them of

their powerlessness over Him.

He will return to Him who has sent Him at the

appointed time, and nothing can hinder that.

When that time comes they will

seek Him in vain, for they will not be able to come to Him.

As they will not

consider the idea that Jesus may be sent by God, the Jews do not understand

what He means.

Does He intend to go and preach to the Children of Israel dispersed

among the Gentiles,

or even to those Gentile nations themselves?

He will not

have time for that, for orders have already been issued against Him.

top

Teaching

on the last day of the feast;

disagreement even among the Pharisees (142-143).

In what He had said so far,

according to what we learn from St. John's summary

of it,

Jesus had answered what was in the mind of those around Him,

and which

they either more or less openly expressed

or else pretended they did not think.

On the last day of the feast He takes the initiative

and teaches them a lesson

full of meaning,

taking His inspiration from the ceremony of the pouring of

water over the altar.

It was the most solemn day of all,

[It was the seventh day,

not the eighth, which had a distinct significance of its own.]

and to it was given

the special name of Hosanna from the psalm [Psalm

cxvii,

25 (cxviii in Heb.).] that was sung during the procession

in which the willow branches were carried.

On this day the prayer for rain

was more insistent,

for the end of this time of supplication was drawing near.

All water, even spring water, comes down from the heavens;

that is why Jesus

likened this pure and limpid element to a gift of God.

In this He was only

following the tradition of the prophets who looked on water poured out upon

a parched land as an image of the new spirit that was to be characteristic

of the time of salvation. [Isaias xliv, 3 ff., etc.]

As Saviour, therefore, Jesus was the bestower of

that water which He would give to those who believed in Him.

We find all that

in His words:

'If any man thirst, let him come to Me and drink.

He that believeth in Me, as the Scripture hath said:

Out of him shall flow rivers of living water.'

[John vii.37 ff.]

The allusion was enigmatic

in character,

but it was clear enough for anyone who understood, as did St.

Paul [1 Corinthians x, 4.],

that Christ was typified by the rock from which miraculous water gushed

forth in the desert;

that miracle was to be renewed in a spiritual fashion

in the days of Messianic salvation,

as had been foretold by Isaias:

'Say: Jahweh hath redeemed his servant Jacob. ...

He hath caused water to flow from the rock and the waters have been poured out.'

[Isaias xlviii.20 ff.]

The Greek version of this passage adds:

'And my people shall drink.'

The evangelist admits, however, that this doctrine was not clear at the time

when Jesus uttered it.

He understood it better later when Jesus revealed it

clearly to His disciples. [John xvi.7.]

He therefore here gives us an explanation of it:

'This He said of the Spirit which those should receive who believed in Him;

for as yet the Spirit was not given, because Jesus had not yet been glorified.'

In the time of the old

covenant the Spirit had intervened in the affairs of the world, suddenly, irresistibly,

bringing light and strength to those heroes and temporary saviours of Israel

such as Othoniel, Gedeon, Jephte, Samson, Saul, men who were sometimes later

deprived of the favour of which they proved themselves unworthy.

But the source

of this favour was not at men's disposal to have recourse to at free-will,

nor was there anyone who possessed the plenitude of the Spirit so that he might

pass the Spirit on to others at will.

Jesus, however, did possess that plenitude,

but His bestowal of the Spirit on others was to wait till after His Passion

and entrance into glory by His Resurrection.

It was well known to all Christians

that by the coming down of the Holy Ghost at the first Christian Pentecost

there had been inaugurated an era of salvation which was permanent and unchangeable.

As for us, who realize how faith in Christ has been the source of love for

God and charity towards men,

of noble thoughts and magnificent deeds,

we cannot

but be struck by the force of this prophecy of Christ which stands there in

the Gospel,

all the more splendid for its isolation.

It may be that Jesus at

the time explained it so clearly that these people of Jerusalem, just as much

moved as formerly the Galilaeans had been by the manner in which He spoke

to them the word of God, repeated in their turn:

'This is the prophet indeed,'

the great prophet whom they were all looking for.

Some went even further and

uttered the word Messiah.

But if Jesus were the Messiah,

what would become

of Juda's prerogative as the Messiah's place of origin?

The people would have

been deceived in attaching their confidence to the word of Scripture.

Was not

the Messiah to be a descendant of the race of David and consequently to be

born at Bethlehem, the cradle of David's family?

Thus the thing was left in

a state of uncertainty,

and meanwhile Jesus was finding more and more partisans,

especially from the ranks of the Galilaeans,

while opposition towards

Him was becoming more timid.

The officers of the law sent by the chief priests

and the Pharisees did not dare to discharge their mission;

accustomed to

deal with a very different type of person,

they were affected by Jesus and

made no secret of this to those who had commanded them to arrest such a man.

But the opinion of common people who had not searched out the texts of the

Law had but little influence on the minds of the Pharisees, who held that

without this knowledge of the Scriptures there could be no real virtue;

the crowd was therefore of no account before God and was the object of His

curses.

Hereupon Nicodemus, who was as learned as any of the rabbis, ventured

on an objection.

Were they going to pass judgement on Jesus without giving

Him a hearing?

Surely that was contrary to the Law!

There ought to be a

fair enquiry into His doings.

An answer had to be found to the objections

of such a rabbi as Nicodemus.

He was bent upon getting at the facts of the

case;

the others replied by appealing to law.

What was the good of an enquiry

about Jesus seeing that no prophet could arise from Galilee?

Was Nicodemus

himself perhaps a Galilaean?

Let him first prove, if he can, that the claim

of this fellow-countryman of his was grounded on the Scriptures!

It appears then that the Pharisees did not know that Jesus had in fact been

born at Bethlehem.

They could always find a way out of a difficulty by exegetical

subtleties;

but God found a more natural way of fulfilling the words of the prophets.

top

The woman taken in adultery (144).

John

vii.53-viii.11.

[There are good grounds for thinking that this incident

is not a part of the original fourth gospel;

but the fact remains that it is canonical and inspired Scripture.

It may have been inserted here as part of the tradition handed down by St. John's

disciples.

But it has rather the appearance of belonging to Synoptic narrative.

In any case there is no reason for doubt with regard to the truth of the facts

narrated.]

{Go HERE for

more on the Perecope de Adultera. katapi ed.}

After these heated discussions all went their way;

Jesus withdrew to the

Mount of Olives where He had friends.

We shall find Him there again later. [Luke xxi.37 ff.]

Early each morning He came to the Temple to teach,

and the crowd flocked about

Him.

He sat as He taught, for the excitement of the feast had died down.

One

day He was interrupted by the arrival of a noisy throng of people.

A woman

had been caught in adultery and had been taken before the Scribes and Pharisees;

it was left to their zeal to see that she should be punished as the Law demanded

and by the proper tribunal.

The fact that she had been taken in the act seemed

to justify summary execution.

From every point of view it was a good opportunity

for finding out what Jesus would say.

He was reputed to be kind in His treatment

of sinners;

He was even said to be their friend.

Would He presume to pardon in such a serious

case as this?

The Pharisees, followed by a violently excited crowd, drag the

woman before Him and describe the case.

Somewhat naively they manifest the

motive that lies behind all this:

'In the Law Moses commanded us to stone such as she.

But Thou, what sayest Thou?'

They do not quote the Law very

exactly:

it did indeed condemn a guilty wife to death [Leviticus

xx.10.],

but it only prescribed

stoning for infidelity on the part of a betrothed woman [Deuteronomy

xxii.23 ff.],

and there were some

who maintained that the punishment was not the same for either case.

However,

as there was greater guilt in the case of a wife than in the case of a woman

who was merely betrothed, it seemed reasonable that the former also should

receive the terrible penalty of stoning.

Hence Jesus did not raise any quibble;

but He does not consider that He is

called upon to pass judgement at all;

He has not come as an official of a

court of justice charged with the duty of giving sentence in accordance with

the law, but to invite sinners to ward off God's judgements by repentance.

With an appearance of having nothing to do with this distressing scene,

He

has stooped down and is writing with His finger on the ground,

as though merely

to pass the time until they go away and leave Him to resume His teaching,

or

as if He wishes to fix certain thoughts in writing.

St. Jerome, having read in Jeremias: [Jeremias xvii.13 (different in Greek Version).]

'They that turn away from Thee shall be written on the earth,'

considered that Jesus was writing down the sins of the accusers.

The comparison was an

ingenious one and made good the gap left by the silence of the gospel text

;

moreover it satisfied curiosity.

It still satisfies some people, but there

are no grounds for it,

for the zealots do

not show any sign that they feel implicated;

all that they show is annoyance

with Jesus for upsetting their calculations by His appearance of indifference.

They obstinately insist on an answer.

Then He says to them:

'Let him that is without sin among you cast the first stone at her.'

In truth it was the

duty of the denouncer to strike the first blow. [Deuteronomy

xiii.9, 10; xvii.7.]

There are cases in which a judge, with shame in his heart, has the duty as

representing the law of condemning a person who is guilty of crimes which he

himself commits;

but that is one of the defects of all human justice.

These people, however,

who were so enthusiastic about the letter of the law, would have done better

if they had first examined their own consciences before showing such zeal.

The older ones among them are suspicious.

Has Jesus read the secrets of their

hearts?

Perhaps He was setting a trap for them in thus showing such apparent

indifference at first, merely in order that He might later intervene with all

the more effect.

These are the first to go away, and the rest of the self-constituted

judges follow their example.

Thus Jesus is left alone with the woman, except

doubtless for His disciples and a few curious lookers-on.

He sits up and questions

the woman who is still terror-stricken.

It would be pleasing to think other

begging forgiveness on her knees.

But Jesus says to her:

'Hath no one condemned thee?'

Still frightened she replies simply to the question:

'No one. Lord.'

Whereupon Jesus says:

'Neither do I condemn thee,'

that is, to the terrible death of stoning.

But there is another judge.

She must take heed:

'Go thy way and sin no more.'

Justice and mercy have met together.

Justice could not

allow a judicial discharge and take no account of the anti-social character

of her crime;

mercy will not agree to condemnation because it sees repentance

in that still terror-stricken heart.

The existence of such repentance is implied

by the fact that He urges a firm purpose of amendment.

top

The light gives testimony

of itself,

The light gives testimony

of itself,

and that testimony is confirmed by the Father (145).

The feast was over.

From now on the crowd ceases to play an active part in

the drama which continues to take place between Jesus and the Jews. On the

first evening of the solemnity four great candelabra were lit up in the Court

of the Women;

the Talmud speaks in moving terms of the way in which the brightness

of the light was shed over Jerusalem and all the surrounding district.

But

as there is no proof that this rite was performed on the succeeding days,

we

cannot say that it was the occasion for the discourse in which Jesus proclaimed

that He was the light of the world.

All that we can suppose is that He may

have heard people speaking of the grandeur of the ceremony, and thus took occasion

to say:

'I am the light of the world;

he that followeth Me walketh not in darkness,

but he shall have the light of life.'

That light, then, would not

be a knowledge in His disciple that produced no fruits;

it would touch the

heart and stir up the will;

it would be a live spark serving as a principle

of moral and religious life,

a ray from the light by which Jesus was scattering

the darkness in which man was striving to find his way. [Luke

i.79.]

In speaking after this fashion, Jesus did not lay down clearly that He was

God,

but surely He was proclaiming Himself as the Messiah.

The prophets had

foretold that the Messiah should be the light of the Gentiles

[Isaias

xlii.6, xlix.6, etc. Le Messianisme, p. 47 and passim.],

as the Scribes well knew.

They must have understood, therefore, that Jesus was claiming to

have been sent by God.

But nobody has the right to bear witness to himself;

Jesus had admitted that of His own accord when He last spoke with them at the

feast of Pentecost;

but He had gone on to add that His Father bore witness

to Him,

as was proved by the fact that the works He did bore the stamp of divine

power.

He now gives them to understand that this stamp or seal was merely a

preliminary guarantee of His mission from God.

When a prophet speaks, he speaks

in God's name ;

but he has to prove by signs that he has been sent by God.

Once he has done

that, it is only from the prophet himself

that his hearers can find out in what his mission consists.

Now Jesus by His

miracles had proved His truthfulness,

for God does not bestow His divine

authority on what is not true.

As Jesus was the channel of truth He was the

Light,

and light has only to shine in order to show itself.

Therefore when

He speaks of His mission they ought to believe Him;

He alone knows whence He comes and whither He is going.

Nevertheless, let them

bear in mind what He has said to them on another occasion [John

v.31 ff.],

namely that God

has given authority to His words.

Since that is so, Jesus is not alone.

The

old adage - too pessimistic by far -

that no notice can be taken of an isolated

witness,

cannot, therefore, be brought against Jesus.

Even if the Law says

such a thing, yet He is still in a safe position with regard to the Law;

His

Father is with Him, so there are two.

As His Father has vouched for His word,

what Jesus says ought to be believed.

The Jews affect to take no notice of the miracles of which Jesus speaks,

the

testimony that has accompanied and accredited His word.

They pretend to understand

Him as offering to show them His Father.

Where is He, then?

If He is speaking

of Joseph, whom everyone regards as His father, then He must be laughing at

them.

If He is speaking of God, then He blasphemes by making Himself God's

Son.

Again Jesus avoids too pointed a declaration.

They may well say that they

know nothing about the Father of whom He speaks.

If only they knew His Son

Jesus, they would know the Father as well.

He left them to understand that

the Son was of the same nature as the Father.

And if such an idea seemed to

them blasphemous,

it was their duty at least to acknowledge that He was sent

by God and so listen to Him;

and in that case they would know His Father better.

The first thing to be done was to trust God's interpreter.

But the Jews refused

to take this first step;

foreseeing already that if they did they would then have to admit that He was

equal to God,

they preferred to put an end to the conversation by arresting

Him.

His hour was not yet come;

the evangelist continually reverts to that.

It is like a plaintive refrain that closes sadly all these conversations.

But

the distinguishing mark of the important teaching given on this occasion is

obtained from the place in which it was given:

it was near the Temple treasury,

in a court where all Israelites were free to enter.

top

The danger of refusing to acknowledge God's envoy (146).

It seems to have been very shortly afterwards that Jesus again pressed upon

the Jews the necessity of making up their minds.

They argue, they find fault,

they shuffle, and the time is going by.

But His time is strictly determined,

and He will not be long before He goes away.

Then they will seek Him (either

at the time of the great siege of Jerusalem, or when they run after false

Messiahs) and will call in vain for a saviour.

But it will then be too late;

they will die in their impenitence with this

added to all their other sins,

that they despised the Saviour sent them by

God.

The Jews are more angered by this mysterious threat than when He had made

it before [Cf. vii.31-36, p. 297 above.],

yet now they understand by His going away He means His death.

But if Jesus is going to God, surely they will meet Him again there!

Does

He mean to destroy Himself and so cast Himself into Gehenna?

To this dreadful

suggestion He simply replies:

'No, if we are never to meet again it is

because we are not of the same world.

Your inclinations drag you down, and

I am from above.

It would be your salvation if you believed in Me;

then

you would be transported to the sphere to which I belong.'

The terms in which

Jesus expresses this, though obscure to people not conversant with the Scripture,

are clear enough to the Jews.

He says to them: 'You must believe "that

I am"';

and it is in these words that the Greek version of the Scriptures

translates the two Hebrew words Ani Hu

(that is 'I He')

by which God

refers to Himself [Deuteronomy xxxii.39; Isaias xliii.10-15.],

meaning 'I am indeed He, He who is from on high, He who

is the Saviour.'

The claim Jesus puts forward in these words is so lofty that

the Jews answer with the sneering question:

'Thou; who then art Thou?'[Cf. Acts xix.15.]

Was it worth while repeating more clearly that of which they must already

have had a presentiment, merely for the sake of replying to an ironical question?

Just as on the former occasion when He was speaking of the epileptic boy [Mark

ix.18; Luke ix.41, p. 274 above.],

so now Jesus gives vent to a kind of sad discouragement,

like a man whose efforts

are disregarded: 'Should I even speak

to you at all?'

Yet He is the mouthpiece of truth;

He says once more that

He speaks nothing but what He has heard from the one who sent Him.

It may

not have been a direct answer,

but it was at any rate a reassertion of His

right to be believed.

For the most part, however, the Jews would not understand.

Nevertheless amongst them were some who were animated by a sincere desire

to follow the way shown by God, and it is doubtless to these that Jesus addresses

a final appeal:

'When you shall have lifted up the Son of Man,

then you

shall know who I am.'

These men of good will were not to die in their sin;

struck by the noble expression

of this Son of Man who followed His Father's will so humbly, they believed

in Him.

Seeing them gather together in order to make known to Him their dawning

conviction, He bids them welcome;

but at the same time He reminds them of

the conditions He has already laid down in the Sermon on the Mount.

His truth

is not just a light and nothing more;

it is not enough to accept that truth.

They must remain in it, that is to say, they must live in it by making their

acts correspond to their belief. [Luke vi.46-49.]

This done there follows a blessed result:

truth that is put into practice grows

within the soul and bestows upon it a power that brings real deliverance and

freedom.

top

In Jesus is the salvation announced to Abraham (147).

These words addressed to the new converts, which seemed so simple, contained

the whole plan of salvation:

to believe in Him who has been sent by God;

to live by His truth and so be delivered from the error which is driven out

by the coming of truth -

and the error in question is chiefly religious error;

and finally to be set free from sin, thanks to the operation within us of that

vital principle which is the truth of Christ.

We know not how far the new converts

profited by this teaching.

But there were others who listened to it, the bitter

adversaries of Jesus, and they began to dispute.

[An exaggerated attachment to the literal sense which was

badly understood has led some to attribute to these new converts a versatility

that is beyond belief.

In the language of that day, 'to answer' often meant no more than 'to begin to

speak,' and for the first time.

The people in question here are new speakers, as St. Augustine has well understood.]

They have well understood

the supreme importance of the principle He has just laid down and they will

have none of it.

There followed a lively dialogue in which words pass from

one side to the other like the quick flash of swords;

it cannot be treated

like a well-prepared thesis which is proved by the analysis of ideas and elaborated

with skill.

The answers made by the Jews, and even those of Jesus, spring altogether

spontaneously from the circumstances of the dispute and are due to the strong

convictions felt by either side, convictions which are irreconcilable.

It

is none the less true that the whole debate turns upon a point of decisive

character,

and this must be made clear if the significance of the exchange

of replies is to be understood.

Jesus offers salvation to those who believe in Him and His mission;

that

is the price of deliverance from sin.

Those who enter on this path must draw

the conclusion that salvation is no longer to be sought from the Law.

The Jews

refused vehemently to accept such a position.

Those who sprang from Abraham

have long been furnished with all that was required for salvation.

Through

Abraham they have God for their Father, and it is for Jesus to be related to

God in the same way as other Jews.

By what right does He call Himself the Son

of God proceeding directly from the bosom of the Father?

To speak thus is

to utter a blasphemy that deserves death.

In this way the Jews close the way

to the truth which Jesus is preaching to them;

they sink deeper still into

falsehood as is proved by the hatred they bear Him, for hatred is begotten

of falsehood, just as charity is begotten of truth.

Therefore they are no longer

children of God, nor even children of Abraham;

rather are they the children

of him who, at the very commencement of history in the Garden of Eden, was

a liar and a murderer, a murderer through his lying.

The Jews hotly return

this reproach of untruth, and they refuse to admit any alteration in the order

of things established since the time of Abraham;

whereupon Jesus immediately allies Himself with Abraham:

not that He is dependent on Abraham, but rather on the ground that Abraham

had placed his hopes in the Messiah, that is to say in Jesus, for He was before

Abraham.

With that the discussion comes to an end.

There is nothing left now

but either to believe in Jesus and worship Him along with the Father, or else

to stone Him as a blasphemer.

Abraham's name appears repeatedly in this discussion, or the Messianism of

the people of Israel begins with him;

Jesus admits that as much as the Jews.

But to their mind the Messiah is at

the most to be only another Abraham, perhaps merely sent to restore the faith

of Abraham.

The idea of associating the Messiah with the worship they pay

to the God of Abraham completely disconcerts them.

The fact is that they

have no deep sense of the supernatural character of the Messiah's work, or

of His mission not merely as a preacher of repentance but as one who comes

in order to destroy sin.

Thus, in the opposition they raise to the claims

of this Saviour who is Jesus, they go straight to this point and begin by

saying that things are not so bad.

The children of Abraham have never been

slaves;

they have therefore no need for anyone to deliver them.

It is unnecessary

to observe that they are not so impudent as to deny that the nation of Israel

was once in a state of subjection to Assyrians, Babylonians, Persians, Macedonians,

and now is vassal to the Romans.

Nor has Jesus made any promise to free them

from earthly slavery.

What the Jews mean is that, whatever may be said of

their past sad history, at any rate since the tribe of Juda (later called

the Jews) returned from captivity in Babylon, they have never bowed before

strange gods.

Of what sort of liberty, then, does Jesus speak?

They forgot that salvation is not to be gained merely by orthodoxy in matters

of faith.

And even if all the descendants of Abraham had been orthodox in faith,

which was far from true in a great many cases, the fact remained that religious

truth had not been able of itself to root out sin;

sin had even grown more

widespread.

Why, then, do not the Jews imitate the heart-felt contrition of

such a man as Daniel?

There never can be pardon for sin without contrition

like that;

it is truth's first step in the way that leads to life.

No; blinded

by their hatred and resolutely refusing the help of Jesus, they tell Him bluntly

that they do not need Him.

It is in reply to this that He tears the veil from what they hide in their

hearts, their desire, namely, to put Him to death.

And despite what they say,

they are in reality the slaves of sin.

This is the very implication of all

their Law with its unending rites of purification;

it is indicated by the

anguished cries of their prophets.

Consequently, they ought to be afraid lest

they be driven out of the Father's house if they do not seek the help of the

Son who abides in that house for ever.

This refusal of Messianic salvation,

which was their nation's supreme hope, comes so strangely from those who are

descended from Abraham, that it seems necessary to conclude that such a refusal

proceeds from an alien spirit.

It is as much as to declare that they have a

father who is not God.

At first the Jews refuse to understand.

'Our father is Abraham,' they repeat.

Then, replies Jesus: 'Do the works of Abraham' and not those of a different

father.

At this thrust the Jews no longer try to shun the issue.

They have

been told that they are not children of God.

But it is well known that their

recent ancestors had not worshipped strange gods, and only a crime of that

sort would have constituted an apostasy of the nation of Israel which had been

joined to its God by the tender bonds of lawful love.

Such an apostasy was

equivalent to a veritable spiritual adultery such as would have made the Jews,

according to the cutting reproach of the prophet Osee [Osee

(Hosea)i.2.], children of a prostitute.

But as this was not the case, these Jews are conscious that they are children

of God.

Jesus then replies:

'If God were your Father, you would love Me, for from

God I came forth.'

He does not accuse them of offering sacrifices to strange

gods, like the gods of the Greeks and the Romans.

But their own Scriptures

tell them of the old adversary of God through whom death came into the world;

and whoever harbours murderous desires towards one who is innocent shows himself

to be the child of that first murderer, the father of lies. It may be lawful

to punish a criminal with death. But what is Jesus' crime?

What sin can they

reproach Him with?

His only crime is that He has told them the truth,

the

truth which they reject because they are not of God.

The Jews are not willing to admit their murderous intentions.

It is, as they

have said once before, merely an illusion on the part of Jesus who is possessed

by the devil;

or perhaps He is a Samaritan.

This was to give tit for tat.

Jesus merely wards

off the thrust.

It is of no use to employ the operating knife on those who

are dead, and these Jews are spiritually dead;

so He offers them once more

the gift of life for their souls:

'If anyone keep My word,

he shall not see death for ever.'

So far every word that had passed between the two parties

to the discussion had been

concerned with spiritual realities;

deliverance from slavery had stood for

freedom from sin;

and here preservation from death was also to be understood

of eternal death.

The Jews, now suddenly changing their point of view and

understanding these things in a material fashion, seize on this last word

of Jesus and try to put Him in a difficult position.

Will He escape bodily

death and cause others to escape it, when Abraham is dead and the prophets

are dead too?

A man who talks in that fashion must think himself greater

than Abraham;

in truth he is possessed by the devil.

Jesus therefore has to protest against this new attack, and in doing so He

must assert His rightful rank.

He modestly excuses Himself for so doing, but

nevertheless He does it, or rather He leaves it to His Father to do so.

Were

He not to reveal the truth, were He to leave them to believe that He does not

know His Father, would be equivalent to taking a way that leads to falsehood;

truth had been given to Him in order that He might manifest it when the time

was fitting.

Yes, then; He is greater than Abraham.

He is the one for whom

Abraham their father had longed;

the one whom Abraham their father, by the light of prophetic vision, had beheld

in the secret future, and seeing Him had thrilled with joy.

So Jesus thought Himself remarkably well-informed indeed concerning Abraham's

feelings!

Had He then seen Abraham, though He was not yet fifty years old?

To this Jesus replies very simply:

'Before Abraham was born, I am.'

This

was the signal for the stones.

But Jesus saved Himself from the stones by leaving

the Temple.

It is impossible not to see a certain analogy between this discussion concerning

the true children of Abraham and what St. Paul has to say on the subject. [Romans

iv; Galatians iii.]

John certainly wrote long after St. Paul.

Shall we say that he is here preaching

Pauline doctrine, that the teaching which flows from this discussion is consequently

a mere product of Christianity which is placed by anticipation on the lips

of Jesus?

If we do then we shall have failed to understand how the two doctrines,

that of St. John and that of St. Paul, are related because they have the same

source.

St. Paul wants to show that justice does not depend on works, but on

faith in Christ.

He proves it by the fact that the faith of Christians is the same as that of

Abraham, who believed in the promise and was straightway declared to be just.

Then, returning from Abraham to the Christian faithful, St. Paul identifies

him as their father.

They are all sons of God by faith in Christ, and having

the same faith as Abraham they are his true posterity, even though they may

not be circumcised.

Arguing in this fashion, St. Paul has drawn a positive

conclusion from what the argument of Jesus teaches only implicitly, and almost

merely negatively.

Our Lord simply showed, in order to answer the objection

the Jews raised from their privilege as sons of Abraham, that they were not

even children of Abraham, since they were not really children of God.

This

is precisely the answer that was called for in the circumstances;

there was

no need for anything to be said about the advantages of those who believe in

Him.

Now St. John had certainly read the epistles of St. Paul;

and it is hardly

likely that his critical judgement would have been so great as to preserve

him, in writing his gospel, from betraying the influence upon him of the triumphant

results of the Apostle's reasoning, or from exceeding the bounds of historical

probability in making use of St. Paul's conclusions, if he had not been guided

in his writing by a vivid recollection of what Our Lord had revealed during

His mission.

Here, then, Jesus affirms His pre-existence plainly and in terms that involve

a declaration of divinity.

The Jews judge that He has said enough to justify

their closing His mouth by stoning Him to death.

Later He will express this

truth still more plainly.

top

The man born blind (148).

The man born blind (148).

On leaving the Temple Jesus was no longer molested;

the plot had failed.

No one could be put to death without the leave of the

Roman authorities,

though in cases where the offender was taken in the very

act of his crime the indignation roused by this fact was looked on as an excuse

for taking the law into one's own hands.

Hence Jesus went about freely and

thus one day met a man who had

been blind from birth.

[Nothing in St. John's text shows explicitly the chronological

connection of this with the preceding incident;

but it seems that there was no great interval.]

In order to call forth the pity of the passers-by the

man was crying out his misfortune.

Of what this misfortune really was he

could have had only a hazy idea, but he knew that it was the frequent cause

of his parents' lamentations.

The disciples, who had not dared to intervene

during the recent dispute, now that they are once more alone with their Master

regain their freedom of speech;

and without any hesitation for reflection

they declare how perplexed they are in face of a hard case like this.

Despite

the abundantly clear and wonderful lesson of the book of Job, the people

were reluctant to admit that suffering would be inflicted on one who had

not merited it.

Now as this man had been born blind, he had not brought the

punishment upon himself by his own sins.

To the disciples this barely expressed

supposition seemed patently false.

Was the fault, then, on the side of his

parents?

They do not know what to think.

Jesus knows that suffering is not always in proportion to sin;

God has His

own designs that are beyond our powers to fathom.

But He knows further that

in this case it is God's purpose to manifest the goodness of His Son

who, being

the light of the world, is well able to cure a blind man.

Whereupon, in order

to test the man's confidence.

He puts a little earth moistened with spittle

on his eyes and bids him:

'Go and wash in the pool of Siloe.'

It was commonly held that spittle put

on the eyes early in the morning was a remedy against eye strain, but no one

claimed the same virtue for mud.

[Among the texts cited by Fouard,

there is one of Suetonius who speaks of spittle (Vespas. VII), and another of

Pliny (H. N., XXVIII, 4).

Mud is only spoken of as a remedy for the special case of tumour on the eyes;

it is in a poem attributed, rightly or wrongly, to Serenus Sammonicus (third

cent. A.D.).

Cf. Poetoe Latinos Minores, by Bahrens, III, v, 214 ff.

Si tumor insolitus typho se tollat inani

Turgentes oculos vili circumline caeno.]

It may be that Jesus applied this curious

remedy merely as a symbol to demonstrate in external fashion the man's defect

of sight. At that time the waters of Siloe were not regarded as possessing

the healing qualities of the pool at Bezatha, but they were the more famous.

Isaias had spoken of them [Isaias viii.6.], and the

Scriptures spoke in several places of the tunnel cut by Ezechias through the

rock in order to lead into the lower part of Jerusalem the waters of the spring

which supplied the ancient citadel of the city.

The water was thus brought

to a pool named Siloe after the tunnel, 'the sender' of the water.

The evangelist

takes the word Siloe as being in the passive voice and interprets it as meaning

'sent.'

Symbolism is displayed here, but symbolism without any mystery.

That,

however, does not give us the right to load the text with symbolism when the

author himself makes no suggestion of it.

Still less have we the right to treat

real incidents as mere symbols when the evangelist's intention, as in the present

case, is to emphasize the glaring objectivity of the facts. Jesus has but recently

demanded belief in Himself as in one sent by God, who alone is capable of taking

away sin;

and now He sees fit to provide by this miracle a type of the pardon

granted in the waters of baptism through faith in Him who is sent by God.

It

was not until later, however, that this lesson was understood.

The man went, washed, and received his sight.

[It is owing to this miracle that the Christian faithful,

and after them the Mohammedans, began to bathe in the pool of Siloe in

order to seek health.

The Empress Eudoxia built a church there, the ruins of which can still be seen.

Cf. Vincent and Abel's Jerusalem, II, pp. 860-864.]

Now it was a Sabbath day, a

day on which it was not lawful to use remedies.

Thus a new complaint was added

to Jesus' record.

But in the then state of affairs one more offence was of

no interest to His enemies except in so far as it was connected with His claim

to call Himself the Son of God.

The miracle was altogether an extraordinary

one, and it came opportunely to give authority to His words, and consequently

to win support for Him in people's minds.

To them it must have seemed that

He who had come forth from the Father and asserted so emphatically that He

knew the Father, must be a better interpreter than the Scribes of what were

the obligations of the Sabbath.

The Pharisees, therefore, will leave no stone

unturned to deny the reality of this cure, the like of which had never been

heard before;

but, as happens when a fact is well established, their efforts

only succeeded in making the truth more plain than ever.

The evangelist's purpose

in relating all the comings and goings that took place is not so much to prove

the truth of the miracle to his Christian readers as to show clearly that the

Jews sinned in the full light of knowledge.

At first it is the neighbours who are slow to recognise the blind man.

But

he says: 'It is really I' - a fact which

no one could doubt.

But how has it happened?

Where is the man who accomplished

it with a remedy which was clearly ineffectual?

As always, the common people

have recourse to their masters, the Pharisees.

They lead the man to them,

and he persists in repeating what he has said before.

Enquiries are made

of his parents, who, to tell the truth, are anxious to keep out of the affair.

They have seen nothing of the matter.

But that their son was born blind and

now has received his sight they are unable to deny.

Let them ask him for

themselves; he is of age.

He is old enough to get out of the difficulty

for himself, they mean;

for the parents are afraid of the Jews.

If they

show signs of believing in Jesus they will be expelled from the synagogue;

that is the penalty determined on by the Jews for any who believe in Jesus,

and it will be applied mercilessly.

The blind man who has been healed is therefore summoned again.

The Pharisees

fully realize their power over the parents and the fear with which they are

inspired;

perhaps their son will be equally amenable.

Provided that he just

consents to say with them that Jesus is a sinner, perhaps they will let the

matter drop.

The man admits with an air of prudence:

'If He be a sinner I know not,'

as though to give more emphasis to the fact of which he is absolutely

certain,

namely that he himself was once blind and now he sees.

But that is

precisely what the Pharisees refuse to admit.

There have been many others since

their time who have refused to admit miracles on principle.

That is the whole

essence of rationalism.

At last the man gets tired of this repetition of questions

which throw doubt on his truthfulness.

Are they really so very anxious to find

out what has happened?

With a touch of mockery he adds: 'Will you also become

His disciples?'

They the disciples of Jesus!

Let him keep the title for

himself!

Then in one word they reveal the whole bearing of the recent discussion

with Jesus.

They do not wish to run the risk of being unfaithful to Moses by

listening to a man no one knows.

Whereupon the man, now that he is thoroughly

exasperated, continues in his former strain:

'When anyone works miracles in Israel, you, the masters, surely ought to know

who he is.

You want me to declare that He is a sinner.

Does His power not prove

rather that He is from God?'

These masters do not like being lectured

and let slip an insult that borders on heresy;

for in reproaching him with

having been wholly born in sins they certainly seem to charge him with responsibility

for his misfortune of blindness.

Their final argument is to drive him off.

But this gave him the opportunity of meeting Jesus who was looking for him.

He was prepared for faith by his courage and gratitude.

He who had cured him

asked him to believe in the Son of Man.

Let Jesus only point him out!

Then

Jesus said to him:

'Thou seest Him;

He who speaks to thee is He.'

The man replied:

'I believe, Lord,'

and fell down at His feet.

And this faith,

being faith in Jesus,

was faith in the Son of God.

The miraculous bestowal of bodily sight now passed into the shadow before

the supernatural shining of that light which Jesus gave to this poor ignorant

man who, according to the Pharisees, was blind to the things of God;

and all

the while the learned grew more obstinate in their pride.

This is what Jesus meant when He said:

'For judgement I am come into this world;

that they who see not may see;

and they who see may become blind.'

These words, in the light of the recent event,

express exactly the idea which we find also in the Synoptists:

'I confess to Thee, O Father ..

because Thou hast hid these things from the wise and prudent,

and hast revealed them to little ones.'

[Matthew xi.25; Luke x.21.]

The Pharisees had given up the thought of violence, but they had not ceased

to watch.

They are there as though by chance.

It is evident that Jesus is referring

to them,

but they seek to force Him to indicate it more clearly so that they

may be seen to have reason for their hatred:

'Are we also blind?'

they ask.

In His reply Jesus touches them on the tender

spot of their vanity as men of learning.

It would not be so bad if they were

blind, whatever they may think or say about the implications of blindness.

The dangerous thing is that they consider themselves discerning and pose as

righteous men.

How can a sin be forgiven when the sinner refuses to admit it?

'Your sin remaineth.'

[John ix.41.]

In these words the Pharisees are to find the stern conclusion of all that

has been said since the Feast of Tabernacles.

top

Jesus the door of the sheepfold and the Good Shepherd (149-150).

Later on, while still at Jerusalem, Jesus again taught the crowd which pressed

about Him.

His words have some connection with what has just been said, though

now they are of a much gentler character.

So, in the words of the prophets,

do the joys of the promised restoration follow close upon the threat of punishment;

mercy follows justice.

We must admit that the foregoing words of Jesus were very severe.

He had made

the hostile Jews understand that He was well aware of the intention to put

Him to death, and He had to give them warning of the consequences the nation

would have to suffer afterwards through their churlish ill-will towards the

Saviour sent to them by God.

The eyes of faith detect in these stern admonitions,

in this use of the knife in order to probe and open the wound, a sincere and

earnest desire on His part to bring about repentance and healing.

But the Jews

were blind to these generous intentions.

They surmised that He would do all

in His power to escape the death which in His sadness He foresaw.

Little did

they know Him!

It was necessary for Him then to open His heart.

Now that He

has warned those who are obstinately hostile to Him,

He turns to those who

are of better dispositions

and tells them with what tender love for men

He

accepts the death He is to suffer for their sakes.

Far from being afraid of

it,

He longs for it,

because He knows that the accomplishment of His work is

to consist in the sacrifice of the shepherd for the sake of his sheep.

When

that is done His murderers in their blindness will run after a saviour of their

own fancy, but it will then be too late;

in despair they will die in their

sin.

Others shall take their place;

already He sees in the future the sheepfold

thrown open to other sheep, all under one shepherd.

The lesson Jesus thus gave touched all hearts and was not interrupted by a

single discordant voice.

Not all were won over,

but so long as He spoke His

audience was doubtless spell-bound,

as are our own souls even yet when we read

His words.

We do not know the precise place where Jesus uttered the words in which He

revealed this great secret concerning His redeeming death.

It may have been

within sight of the Desert of Judaea, for He begins with a comparison drawn

from the life of a shepherd, a real parable with a few allegorical touches

relating to persons or circumstances connected with the religious life of

Israel.

The desert was inhabited, as it is to-day, by nomads dwelling in

tents who went from one hill to another in search of the scanty traces of

pasture.

In the day-time each drives the sheep or goats belonging to him,

unless he be rich enough to hire the services of a shepherd.

But at night

all the flocks of the tribe are shut up in a fold which is sometimes enclosed

by a wall.

Only one shepherd is required to guard the enclosure.

When morning

comes he opens the door to the other shepherds,

and each one on entering

gives a cry that his flock recognizes,

and they follow him at once.

If one

of his sheep should stray,

he brings it back to the flock by calling its

name,

a name which he bestows on it from its colour, agility, obedience,

or tendency to stray.

A thief who had made up his mind to get into the fold

at night would certainly not knock upon the door and so attract the shepherd's

attention;

rather would he climb over the low wall or fence.

And if he succeeded

in carrying off some of the sheep,

they certainly would not follow him of

their own accord,

for they would not be used to the sound of his voice or

his peculiar call.

Jesus reminds

the Jews of all this.

They did not understand what He meant by it, and at first it was hardly possible

for them to do so.

No parable is clear until we know to what it is to be applied;

but Jesus is

about to tell them.

We, of course, who have had the benefit of Christian education,

cry out:

It is Jesus who is the Good Shepherd.

But let us wait a little.

The comparison made by Jesus supposes that there are good relations between

the sheep and their shepherd, but it also lays emphasis on the contrast between

true shepherds who enter by the door, and thieves who climb over the wall.

Thus the door of the sheepfold becomes the sign of the good shepherd.

Jesus

says then: 'I am the door of the sheep.'

Before He came no one had passed

through that door;

others who had come were thieves, and consequently the

sheep had paid no heed to them.

But others shall come and they shall enter through Him, the true door, and

shall lead the sheep out to pasture.

These last are unmistakably His disciples,

those who believe in Him and teach His doctrine.

Who, then, were the robbers?

It is obvious that Jesus does not intend this

to be a description of Moses or the prophets, or even of the good kings of

the past.

There had always been good shepherds in Israel as well as wicked

ones, veritable stealers of the sheep. [Zach. xi.15-17.]

But the parable has not those long

past days in view.

Even in Jesus' own time the Pharisees, who thought themselves

shepherds even if they were not so in reality, had managed to get themselves

accepted by the sheep.

It must be remembered that here Jesus is speaking in His role of Messiah;

therefore those whom He is blaming are persons who have given themselves out

unwarrantably as Messiahs, like for example Judas the Galilaean, Simon one

of Herod's slaves, Athronges, and others still. [Le

Messianisme, p. 18 ff.]

To satisfy their ambition

they had tried in vain to arouse the people;

or if they had succeeded through

their religious fanaticism,

the only consequence was that their followers had

been massacred.

Now Jesus had no mission of this kind;

on the contrary He

had come that men might have life, and life in abundance.

Hereupon, with the flexibility of this parabolic figure of speech which, like

the riddle, loves to baffle the attention in order to cause pleasure by surprise,

the parable of Jesus takes a different turn.

As He has contrasted Himself with

false shepherds,

He now goes on to say what we were expecting:

'I am the good shepherd.'

But then comes something which goes beyond all that might have been expected or hoped for:

'The good shepherd giveth his life for his sheep.'

How different from the hireling who flees at the sight of the wolf!

Then again:

'I am the good shepherd ...

and I lay down My life for My sheep.'

The sheep are those who know Him and are known by Him.

All the knowledge in

question comes down from the Father.

He knows His Son and His Son knows Him;

the Son knows His sheep and His sheep know Him.

As already shown in the parable,

it is Jesus who first comes to seek His sheep and to make Himself known to

them in the sheepfold of Israel.

But there are others who have

never heard of Him;

them, too, He will seek out, unil there shall be but one

flock and one shepherd.

There was no difficulty in seeing this wonderful prospect of the future, for

the prophets had often spoken of it:

the Messiah was to be the light of

the Gentiles, joining them to Israel in the worship of the one true God.

One point, however, still seemed obscure even to the extent of contradiction.

How could Jesus do His work as a shepherd once He had laid down His life for

His sheep?

This He now reveals.

He will lay down His life at His Father's

command,

but His divine being, derived from the Father who begot Him,

eternally

guarantees that His sacrifice will attain its purpose.

Not only has He power

to lay down His life for the salvation of the world,

but He also has power

to take it up again and bestow upon the world that which His life has bought.

And even while He is thus revealing His greatness,

the Son emphasizes His submission

to the Father,

as though He wishes to quieten the scruples of His Jewish hearers

by thus subordinating Himself to the pleasure of the God of Israel

and to those

hopes of Israel which His mission confirms:

'This commandment have I received of My Father.'

All had listened attentively.

Many of His hearers are unmoved by His words

and say once more that Jesus is possessed by the devil;

thus they confess

that they are insensible to love and merit the judgements of justice which

they bring down upon themselves.

But there are others who are conscious that

His words proceed not from the spirit of evil but from the Spirit of God, and

that they must be believed, seeing that they have been confirmed by a miracle

like the cure of the man born blind.

When the Greek and Roman Gentiles were brought into the one fold which held

the revelation granted to Israel, this picture of the Good Shepherd appealed

to them greatly;

it is often found drawn on the walls of the catacombs in Rome.

Those early

artists were full of faith, but they had received their artistic training in

the school of the mythological painters;

it is suggested, therefore, that

they got their inspiration from the wonderful picture of Hermes carrying the

ram.

But the meaning of that was very different, for it was the ram, not the

shepherd, which was the victim of sacrifice.

This pagan imagery had never penetrated

intoJudaea, moreover, while the Sacred Scriptures

were full of allusions to the Good Shepherd that God proved Himself to be of

old, and that the Messiah was destined to be in the future.

Scholars may,

if they please, look in pagan religions for notions that are analogous to

the truths of Christianity, though to tell the truth they do not find many

such notions that will stand examination;

but they exceed all bounds when

they maintain that the author of the fourth gospel drew his inspiration from

such notions -

and then attributed them to Jesus.

They would do well to keep

in mind that ironical proverb of Attica:

Taking owls to Athens!

Israel

had often spoken in praise of the Good Shepherd,

[See Psalms (Hebrew numbering), xxiii; Ixxiv.1; Ixxviii.52;

Ixxix.13; Ixxx.2; xcv.7; Isaias xl.11; Jeremias xxxi.10; Ezechiel xxxiv.11-16;

also the so-called Psalms of Solomon, xvii.45.]

though she never knew that

He was to lay down His life for His sheep.

That revelation comes as something

new even in the gospel.

[Always excepting John vi.51 (Vulg. v.52), but which is

not so plain-spoken.]

Jesus will later return to it.

END OF VOL. I

The Mayflower Press, Plymouth, William Brendon & Son, Ltd.

top