CHAPTER IV: FORMATION OF THE DISCIPLES AND MINISTRY, CHIEFLY OUTSIDE GALILEE

HOME | Contents | Introduction | 111-3.Pentecost at Jerusalem | PART II.

THE first year's preaching ends in failure, despite the evergrowing enthusiasm

of the people;

and it is St. John,

the revealer of the Word Incarnate,

the

evangelist who is accused of transforming the whole gospel in order to glorify

the Word,

it is St. John who declares to us that failure

along with its causes

in the plainest terms.

But the truths that come most into conflict with our

fallen nature

are the truths that are most salutary for the soul.

Henceforward,

at any rate, there was no more room for illusion;

the disciples are forewarned.

From this time

Jesus was to devote Himself more fully

to the formation of

those who are called to carry on His mission;

His own special work is to consist

in the surrender of His life.

During the days now to come He will plainly foretell

both His Passion and His Death,

and He will declare what are the hard conditions

under which men must work out their salvation.

But although He is to suffer

and to die,

nevertheless the kingdom of God is to be established after His

Resurrection,

concerning which He now speaks openly.

Galilee has refused to

understand what kind of Messiah He is;

He now leaves Galilee in order to visit

the northern frontiers of Palestine,

and afterwards Jerusalem, Judaea, and

Peraea.

It is not any fear of Herod which decides Him to go away:

He knows

only too well that He will receive still less consideration at Jerusalem.

But

it is there principally, face to face with the rabbis,

in the very centre of

worship and religious teaching,

in His Father's temple,

that He is to reveal

what He is.

We have seen that during this first year He went up to Jerusalem for the Pasch.

Did He return thither for Pentecost and the feast of Tabernacles?

It may have

been so, but at all events St. John says nothing about it.

[We follow the order given by the tradition of the ancient

gospel harmonies which places the events of Chapter VI before those of Chapter

V.]

Either these journeys

never occurred, or if they did, nothing happened worthy of note for the progress

of the gospel.

To the mind of St. John, this first year was sufficiently accounted

for by the ministry in Galilee.

During the second year, however,

he brings

Jesus to Jerusalem for the feasts of Pentecost, Tabernacles, and the Dedication;

and each of these pilgrimages is made the occasion of some fresh development

in the revelation of Christ's divinity.

Surprise is caused by these two different forms of teaching used by Our Lord:

one in Galilee, represented by Peter's catechesis as given us by St. Mark;

the other chiefly at Jerusalem, shown to us in the recollections of St. John.

We are far from saying that St. Peter did not accompany his Master to the Holy

City;

but he was certainly less at home there than John,

who had -

we do not

know how -

connections at Jerusalem even amongst the hierarchy.

Perhaps, too,

Peter thought that the conversations

or, to tell the truth, the disputes into

which Jesus was drawn by the hostility of the Pharisees,

were of too subtle

a quality to serve as matter for his own daily preaching to the people.

There

is no reason also why we should not see something of St. John's own genius

in the manner in which Jesus' teaching at Jerusalem is presented.

But in the

other gospels too the revelations of this second year are more profound,

there

is more light thrown on the person of Jesus,

on His own sacrifice,

and on the

sacrifices which He demands on the part of others.

We are in a loftier region,

in a more rarefied atmosphere.

The determination of His enemies becomes more

marked,

the devotion of the disciples more deliberate though still imperfect,

and it is gradually strengthened by closer communion with their Master.

He

is engaged in founding the Church instead of that earthly kingdom with which

He will have nothing to do.

top

I. PENTECOST AT JERUSALEM

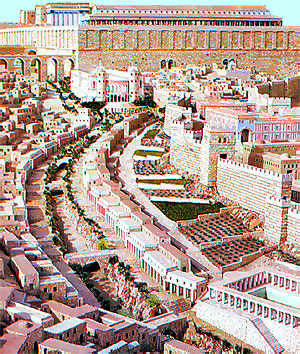

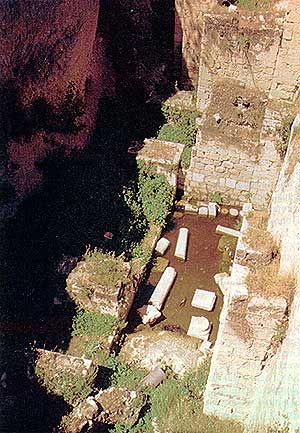

The pool of Bezetha at Jerusalem. Jesus heals a sick man (111-3).

The pool of Bezetha at Jerusalem. Jesus heals a sick man (111-3).

The Paschal season, already near when Jesus multiplied the loaves, was spent

by Him in Galilee.

Afterwards He went up to Jerusalem for some feast of the

Jews which is not described more fully, but cannot be other than Pentecost

since it was followed by the feast of Tabernacles.

'The feast of Weeks,' so

called in Hebrew because the people then offered in the Temple the first-fruits

of the harvest ripened during the seven weeks after the Pasch, was named Pentecost

in Greek, an equivalent name since it means (the feast) 'of the fiftieth day.'

By the time of Jesus an historical commemoration had been attached to this

feast, namely that of the promulgation of the covenant on Sinai.

It therefore

provided an occasion for renewing one's zeal for the observance of the Law.

Now it happened that Jesus, as He was either entering or leaving the Temple,

went into the porch or colonnade surrounding the pool situated near the city-gate

called the Sheep-gate, so named because by that way the sacrificial lambs were

brought to the Temple.

Now it happened that Jesus, as He was either entering or leaving the Temple,

went into the porch or colonnade surrounding the pool situated near the city-gate

called the Sheep-gate, so named because by that way the sacrificial lambs were

brought to the Temple.

This pool was in the gorge which of old had served as

a protection for the northern wall of the Temple, and it was cut out of the

side of a hill which had recently been included within the city-walls.

The

hill was called by the Aramaic name Bezatha, and the pool naturally bore the

same name.

It was oblong in shape, surrounded by four colonnades and divided

into two equal squares by a fifth colonnade.

This arrangement, which we are

able to recognize with certainty from the excavations,

[Cf. Jerusalem (Vincent et Abel), II, 4, pp. 685

ff. and PI. 75.]

throws light on the

passage in St. John, who thus shows himself to have been perfectly acquainted

with the place.

[He says that the pool is at Jerusalem, and that is quite

correct, for there is no reason to doubt that it was still there during the

period of Roman domination in Palestine.

People still believed in the miraculous efficacy of its water

(cf. op. cit., p. 694).

A certain healing power was attributed to the water

and was probably more active when the fresh water, held back by a sluice, entered

the pool and caused the water to bubble.

The Jews were no doubt disposed to

attribute a supernatural power to the water,

and that opinion has crept into

the gospel text by means of a gloss, verse 4, which we do not hold to be authentic.]

Jesus

found there a great number of sick people, blind, lame, and halt, all begging

for alms, though they were there in the hope of something better than alms.

In fact they hoped for a cure, for the one at all events who should first succeed

in throwing himself into the pool after the water was moved.

[Strack and Billerbeck (II, p. 454) quote the Rabbi Tanchuma

(circa AD. 380), who speaks of a man cured of the itch by bathing in the lake

of Tiberias at the moment when the fountain of Miriam began to gush up to the

surface of the water.

That was regarded as a miracle, and no doubt they believed that only one person

could benefit each time.]

Among the cripples

Jesus saw one who was a paralytic, according to the description of ancient

tradition.

Whatever was his malady, he was incapable of moving at least to

this extent that, by the time he had painfully got ready to go down into the

pool at the bubbling up of the water, someone else would be there before him.

Jesus offers to heal him,

and without even requiring from him that act of faith which He saw him prepared to make,

said: 'Arise, take up thy bed and walk.'

The man, conscious that he was cured, picked up his pallet and went away.

Now it was a Sabbath day.

This remark is not made by the evangelist out

of a mere love for exact detail:

it is of weighty importance.

Not only had

Jesus worked a cure on the Sabbath day without urgent need, but, what was more

serious.

He had commanded the healed man to carry away his pallet.

Now it was

considered unlawful even to wear ornaments on one's dress that it might be

necessary to fasten or unfasten on the Sabbath.

[To this the rabbis added casuistical subtleties about the

gravity or lightness of the fault.

Jeremias (xvii, 21 ff.) had indeed forbidden the carrying of burdens, but for

purposes of trade (cf. Nehemias xiii.19 ff.).]

Such a violation of the customs introduced by their forefathers could not

be borne by the Jews, that is to say, by those Pharisees and Scribes attached

to strict traditional observance who were the adversaries of Jesus.

The man

doubtless considered that one who had power to cure him must be a good interpreter

of the Law.

But who was He?

He does not know what to reply to the Jews who

question him minutely.

So little intention had Jesus of parading His power

that He had vanished in the crowd.

Later the paralytic finds Him in the Temple,

ascertains His name and informs his questioners.

At once they remember that

Jesus is an old offender of whom they had somewhat lost sight.

[Matthew xii.14, etc.]

Seeing their displeasure,

He shows Himself quite willing to explain His conduct:

'My Father worketh until now, and I also work.'

The origin of the institution of the Sabbath was due to the fact that God rested on the seventh day.

[Genesis ii.1-3; Exodus xx.11; xxxi.17.]

Instructed Jews, however, were quite aware that this

rest of God was only a figurative expression to mark the stability of the

order which God had brought into the world.

God is ever working, otherwise

everything would crumble into nothing.

Like God, Jesus also works, interpreting

the Sabbath in the spirit in which it had been instituted.

There was nothing

blasphemous in His words when understood in this way, not even for the Pharisees.

But they interpret His words as meaning that Jesus claims the right to work

as the equal of God:

and if He were only a man, as they thought Him, that

would have been blasphemy.

They will later condemn Him to death for that

very reason.

But the time had not yet come for making that solemn declaration of His equality

with God;

so instead of answering: 'It is true: I am equal to God ' - or

rather:

'Because I am God I am equal to the Father' -

He merely asserts His

right as one sent by His Father.

His reasoning, however, far from excluding

the fact of His divinity,

on the contrary takes it for granted,

since the one

who is sent is the only Son of the Father;

yet He has received in His human

nature certain prerogatives which are consequent on the personal union of that

nature with the divine nature, and it is on these prerogatives that He now

insists.

Such is St. Cyril of Alexandria's interpretation of this discourse,

in which Jesus seeks to calm the anger of the Jews by adapting His language

to harmonize with that human aspect of His which was due to a nature really

human, but a human nature which was at the same time endowed with the highest

privileges.

Jesus could hardly begin more modestly

than by saying, as He does, to those who accuse Him of daring to set Himself up as the rival of the Father:

'The Son cannot do anything of Himself but what He seeth the Father doing ...

for the Father loveth the Son and sheweth Him all that He doth ...'

[Nevertheless, it has been possible to interpret this phrase in the trinitarian

sense, for the divine, uncreated, eternal nature of the Son, identical with

the nature of the Father, is yet received from the Father, who is the sole

principle of the nature of the Son.

Filius habet potestatem a Patre a quo habet

naturam. (St. Thomas, la, Q., 42, a, 6, ad i.)

But taking the discourse altogether,

the Son is speaking as exercising the mission of His Incarnation.]

The rather long discourse uttered by Jesus on this occasion was free from interruption,

which we may take as a sign that His words did not seem too bold to the mind

of His Jewish audience.

He does not proclaim Himself to be the Messiah;

that title, as understood by the Jews, would be at variance with His mission.

He is, if they like to think so, a spiritual Messiah such as He had revealed

Himself in Galilee, and the Son of God to whom the Father shows His works

because the Father gives Him power to perform these mighty miracles.

The

chief work He has come to do is that of bestowing life on those who seem

to be alive, but who are dead in the sight of God.

Let them believe that

He is sent by God, let them honour the Son, and they will have eternal life

within them.

The Son communicates to them the life that He has received from

His Father, and He will judge them in the name of the Father.

That voice

of the Son, which now begets in them spiritual life by means of faith, is

the same voice which will be heard once more at the resurrection, whether

it be resurrection unto life or resurrection unto death.

Here we recognize again the teaching of the first part of the sermon on the

Bread of Life,

though now without the symbolism introduced by the multiplication

of the loaves.

The idea of Jesus as judge adds nothing essential to that teaching,

for those who believe are not judged because they have already passed from

death to life.

The distinctive note of the present discourse is this revelation

of the intimate relationship that exists between the Father and the Son, a

revelation which prepares the way for the declaration of identity of nature

in Father and Son;

a declaration, however, which in no way militates against

that relationship of Father to Son and Son to Father which implies that they

must be two distinct persons.

In the latter part of this discourse Jesus points out to the Jews the reasons

why they ought to believe in the mission that He has received simply under

His character as Son.

The grounds of such a belief are not capable of being

arrived at by a process of reasoning from self-evident principles, for the

mission of the Son depends solely on the Father's will.

It was a question of

fact, and as in every question of fact there was no other course but to examine

the testimony of witnesses. There was first the testimony of John the Baptist,

of whom Jesus speaks in the past tense;

John was therefore already dead.

[Here we have a very important indication and reason for

assigning the Bezatha incident to the Pentecost following John's death.

He was beheaded shortly before the Pasch.]

After his death the Jews seem to have become

more favourably disposed towards him,

doubtless because he had died a martyr's

death in defence of the Law.

But Jesus reminds them how John had borne witness

to the truth by pointing to the one who was to come

after him.

A mere man's testimony, however, was not in itself sufficient in the present

case, though the testimony of this last of the prophets was not without weight

in Israel.

There was a further testimony which was of a more conclusive character,

namely the witness of deeds, that is to say the testimony of miracles by which

men might recognize that a person was sent by God.

Even at Sinai their ancestors

had not seen God Himself nor heard His voice.

This very feast of Pentecost

which the Jews were now celebrating could not but recall to their minds the

memory of Moses, the great mediator between Israel and God, whose testimony

was recorded in the Scriptures where it stood for the very testimony of God

Himself.

Since the Jews are so diligent in searching the Scriptures,

it ought

to be evident to them that the Scriptures also bear witness to Jesus.

But the

fact is that only too often the chief motive of their studies was to obtain

among one another a reputation for learning, and they were far from being inspired

simply by the love of God.

Therefore Moses, the greatest of those to whom God

had entrusted His word, the very prophet in whom they set their hopes, Moses

himself shall be their accuser before God:

'For,' as Jesus adds, 'he wrote of Me.'

The Synoptic Gospels reason in precisely the same way, though in different

terms and in a less didactic manner.

John's testimony was indeed precious,

but after all it was rather Jesus who had given authoritative testimony to

John [Matthew xi.7-10, Luke vii.24-27.],

than John to Jesus.

The Father had given testimony to Jesus by means

of all those miracles enumerated by the Synoptists which St. John barely mentions,

and by those expulsions of the devil concerning which the fourth gospel is

completely silent.

All four gospels, however, are careful to make that appeal

to the testimony of Scripture which Jesus here lays down as a principle, though

the Synoptists,

St. Matthew especially [Matthew xxi.42;

xxii.43 and parallels.],

do so in a much plainer fashion than

does St. John.

St. Paul could not help seeing how in the person of Jesus were

thus linked up together the Old and the New Covenants.

The error of Marcion

in making the Old and New Testaments opposed one to the other is therefore

without a shred of evidence.

And at this time, when, to the great scandal of

the Jews, so many impostors were publishing absurd claims to divinity based

on old pagan fables, Israel ought to have felt herself reassured when she saw

how strictly Jesus, God's ambassador, adhered to the words spoken of old by

God.

It was no new religion that He was putting forward;

He did no more than

include Himself in the worship paid to the Father, whose Son He was.

What He

proposed to the Jews was a development of their faith,

parallel with the development

that had taken place in their Law.

And all this He does with an infinite reverence

for His Father

from whom He derives all that He has and is,

whose will is His

law:

His Father,

the source of life

and last end

unto which all things are

led by the Son.

The only effect produced by all this on these ill-disposed Jews was that they

made up their minds to do Jesus to death.

He therefore retraces His steps to

Galilee. [John vii.1.]

top