CHAPTER III: THE MINISTRY IN GALILEE

7. THE MISSION OF THE APOSTLES AND THE ALARM OF HEROD ANTIPAS

HOME | Contents | Chapter III: < Part VI | PART VII: 101-2.The mission of the twelve apostles | 103-4.The death of John the Baptist | Herod Antipas and the Baptist's death | Part VIII>.

The mission of the twelve Apostles (101-102).

Luke ix.1-6; Mark vi.6-13; Matt. x.5-16; xi.1.

Jesus does not stop preaching because He has been cast out of Nazareth by

His compatriots.

On the contrary He wishes the good news of the kingdom of

God and the call to repentance to be more widespread,

and He therefore calls

the Twelve and sends them out to preach two by two.

This first mission serves

to foreshadow what will be their apostolate after His nation has handed Him

over to the Gentiles.

But for the time being it is to His own nation that Jesus

is still devoting all His care,

for it is this people that He has come to call,

the appointed guardian of the promises and of the Scriptures.

It is to them,

therefore, that He now addresses the word of God by means of His disciples.

Hence He bids the Twelve not to take the way of the Gentiles nor to enter the

cities of the Samaritans,

but to go rather to the lost sheep of the house of

Israel.

It is not the object of their mission to draw attention to

Himself.

He does not commission them to recruit partisans for His messianic

claims.

And He counts so little on their enthusiasm for turning to good account

the miracles He Himself has worked that He gives them power to work the same

wonders themselves:

casting out devils, healing the sick-and St. Matthew

even adds raising the dead.

The impression He had made, deep as it was, was

in danger of fading away.

But that did not matter.

What did matter was that

God's call should resound throughout the whole land of Israel:

'Repentance!

For the Kingdom of God is at hand.'

Time was short and it was

necessary to act quickly.

Yet Jesus does not call on His disciples to use haste.

He gives them instructions which take their character from the country and

the situation in which they were uttered, but the substance of them is adapted

to all times, places, and circumstances.

In a word, two things are required

for one who would succeed in such a mission as that with which He charges

His disciples:

disinterestedness and a whole-hearted devotion to the task.

Disinterestedness must be beyond all cavil, carried even to the extent of

poverty;

and not a mere show of poverty,

but a poverty that is voluntarily

chosen.

[Here we follow St. Mark's text because it brings out the

ideas in stronger relief than the text of Luke and Matthew.

Moreover, it seems to represent better the actual words of Jesus, with its alternation

of prohibitions and permissions.

In Luke and Matthew the prohibitions are given in a much more unqualified manner.

The essential thing underlying it all was to make clear what was to be the poverty

of the missionary.]

A traveller in Palestine always took with him a few flat cakes of

bread for the journey

and wrapped a few coins in his head-cloth or in his girdle;

if he rode an ass he would put on two coats as a protection against the cold.

But the disciple must take neither bread nor money at all, and no second coat;

he must travel on foot, and he is allowed therefore to provide himself with

the poor man's staff to help him along;

for foot-gear let him wear simple sandals,

strips of leather attached to the sole of the foot by a strap.

This meant having

the appearance of a beggar.

But even the professional beggar carries a wallet

that he has every intention of filling,

though he might be begging in the name

of religion.

We read of a mendicant who begged in the name of Atargatis, a

Syrian goddess, and who was able to render thanks to his patroness for his

gains.

We are interested to learn that he filled his wallet seventy times during

each of

his rounds.

[Taken from an inscription published in 1897.]

The disciples are to have no wallet to fill.

Abandonment of themselves

to the care of Providence must be their daily rule, or rather the rule of

each moment.

Having arrived at some village,

the disciple who labours in preaching the

kingdom of God must give all his attention to that duty.

As to the question

of hospitality,

that has always been the rule in the East.

At the very least

there will be a guest-house for the reception of travellers.

But a public place

of reception like a caravanserai, with its continual bustle of arrival and

departure, the travellers preoccupied by their own affairs, the servants not

infrequently indulging in behaviour so coarse as not to be free from viciousness

-

such a place was in no way suitable for treating of the affairs of the soul.

The Apostles are therefore to choose a private house:

it is hardly believable

that no one at all will ask them in.

Once invited, they must remain at that

house until they go on to another town.

Perhaps other people may come to offer

an invitation.

Acceptance would mean exchange of compliments, waste of time,

hurt feelings.

They can see everyone by keeping to one house;

for though the

Oriental is very jealous of the privacy of the rest of his house,

the reception

chamber is at any rate thrown open to all-comers.

All through the day and the

whole evening there will be free entrance for anyone who wishes to talk with

these strangers about the expectations that are stirring all hearts in Israel.

It may happen, however, that some town may not be disposed to receive the

messengers of good news;

or else, when curiosity is satisfied, may refuse

to believe them.

If the inhabitants behave in that way it will be equivalent

to bearing witness against themselves that they are not of God's people.

When

a Jew returns home from a visit to a Gentile land -

and every Gentile land

he regards as unclean -

he spares the sacred soil of Palestine all defilement

by shaking the Gentile dust from his feet before entering.

Thus the disciples

also are to ' shake off the dust from their feet for a testimony against' such

froward people.

Here again Jesus struck the highest note of human heroism.

His Apostles were

to serve as the model for all future generations of Apostles.

Some of His admonitions

are adapted to the circumstances of the time and are not

to be taken as literally binding for all times and circumstances.

But it would

be idle to undertake the conquest of souls without first being possessed

by a desire for their salvation so absorbing as of itself to exclude all

self-seeking.

That is what St. Dominic and St. Francis realized so well:

the apostolate requires poverty, and poverty is a preparation for the apostolate.

Thus the Apostles set out on their mission of preaching, driving out devils,

healing the sick.

St. Mark adds that they used anointing with oil on some who

were sick and healed them. [Mark vi.13.]

Doctors in the East always use oil, especially

for dressing wounds.

As Mark is speaking of the sick, and of apostles, not

doctors, the anointing to which he refers was surely in the nature of a rite

used for obtaining a cure.

Just as Jesus did not baptize, so neither did He

use this rite;

but His disciples would not have taken it upon themselves to

employ it unless He had prescribed it to them.

The Church has regarded this

practice of the Apostles as a prelude to the sacrament of Extreme Unction,

[Council of Trent, Sess. XIV, Doctrina de sacra extr.

met., Cap.I : Sacramentum ... apud Marcum quidem insinuatum, per Jacobum

autem Apostolum ac Domini fratrem fidelibus commendatum ac promulgation.]

to which St. James alludes more plainly. [James v.14 ff.]

Rationalists deny the sacred character

of this anointing evidently because they are unaware of the firm conviction

of the early Christians regarding it;

for the exaggerated importance given

to the anointing of the sick by the Gnostics and Mandaeans

[Cf. Revue

Biblique, 1927, p. 509.]

shows clearly

that, at any rate, they made no mistake about the significance it had in the

New Testament passages.

It was not, however, the intention of Jesus so to bind

up the power of the Apostles with this rite of anointing as to make a clear

distinction between theirs and His own sovereign power.

Just as the work of

baptizing was left to them so also, in thus preparing them for their future

ministry as pastors, He was preparing to entrust to their care the grace granted

through the sacrament of Extreme Unction to the sick members of the Church

which He was founding.

top

The death of John the Baptist (34; 103-104).

Luke ix.7-9; iii.19-20; Mark vi.14-29; Matthew xiv.1-12.

The mission of the Apostles must have occurred during the winter,

since it

came to an end before the Paschal season.

[As we shall see in John vi.4.]

When the work of sowing the fields was over in Palestine men folded their

arms and sat down to wait for the harvest.

That was the favourable time for

long talks, when everybody was at home.

The disciples sent out by Jesus had

stirred up the people's hopes on nearly all sides.

Consequently rumours began

to reach the petty court of Herod Antipas, the tetrarch of Galilee and Peraea.

Everybody had his own opinion about Jesus,

and in these opinions no one gave

much thought to the Messiah,

for was not he to manifest himself in a halo of

glory?

But as Elias had to precede the Messiah and confer the royal unction

upon him,

perhaps Jesus was Elias the forerunner come down from heaven whither

he had been taken up.

According to others, who were not so enamoured of the

extraordinary and preferred unquestioned historical tradition,

Jesus was simply

a prophet like all those whom Israel had heard in the past.

Herod called to

mind that other man who had recently stirred up popular feeling, namely John

the Baptist.

But him he had beheaded.

There were times when he reminded himself

of that brutal deed and wondered who Jesus could be.

All around him there were

whispers-for people dared not speak it too loudly -

that John had risen from

the dead:

that although he had worked no miracles during his lifetime,

now

he had come back from the dead with a divine power at his command.

And Herod,

when remorse assailed his irresolute soul, would himself expect to see his

victim rise again before his eyes.

It was the recording of these half-formed

opinions that led Mark and Matthew to relate the account of John the Baptist's

imprisonment and death.

That imprisonment had served as the signal for Jesus to begin His own ministry,

and here we learn the reason for John's being cast into prison.

It was but

one of the many

tragedies which had stained the palace and family of Herod the Great with so

much blood that even Augustus was nauseated. [See above, p. 47.]

The doom that lay upon the

sons of Atreus was more striking perhaps, but not more bloody, than the plots

which formed around that tyrant, with his jealousies, his suspicions, and

the feminine intrigues in the midst of which he floundered and from which

he freed himself by cutting off heads.

Herod Antipas was his son:

he had

inherited his father's ambition but not his indomitable energy.

He had married

Herodias, his brother Philip's wife, says St. Mark,

a thing stigmatized by

the Law as adultery. [Leviticus xviii.16; xx.21.]

In those days John was preaching repentance.

But if

such licentiousness was treated with servile respect how could men presume

to hope for God's mercy?

John did not hesitate.

We do not know whether Herod

asked to see him in order to seek his opinion on the matter or whether John

approached the tetrarch on his own initiative, acting under the inspiration

of that Spirit of righteousness which animated the prophets of old;

but at all events he bluntly declared:

'It is not lawful for thee to have thy brother's wife.'

To silence him Herod threw him into prison.

To have revealed

his real reason for this would have been equivalent to publishing what was

an unpleasant rebuke.

In view of the excitement caused by John's preaching,

a very plausible excuse was provided by a pretended fear of some revolutionary

movement that would be displeasing to Rome.

But obviously the tetrarch wanted

to satisfy the hatred of Herodias who was feeling uneasy.

She was not satisfied:

only death would silence that voice.

For John went on

speaking.

In irons he was not greatly to be feared;

but all the same he was

calling down the judgements of God, and Antipas, more of a Jew than his father,

was troubled by this.

Between Herodias and John he was at his wits' end;

he

literally saw no way out of his perplexity.

[ὴπόρει according to the reading in three MSS.

The Vulgate exaggerates in saying that Herod did many things by John's advice.]

Herodias was on the watch for a favourable opportunity.

Like all Oriental

princes, Antipas was in the habit of keeping his birthday with much festivity.

On this occasion everything was as usual,

banqueting, much drinking, flute-players

and dancing girls,

when suddenly a young girl of

the race of Herods and Hasmoneans,

the daughter of Herodias by her first husband,

was seen coming in dressed as a dancing girl.

Such obliging kindness along

with the hesitating grace of her movements, which professional habit would

have rendered more confident but at the same time would have vulgarized,

also her desire to please, touched Herod and unsettled him.

The enthusiasm

of his courtiers completed his infatuation.

Nothing seemed too costly to

reward such charms.

The traditional phrase:

'Ask me for the half of my kingdom'

was only a meaningless exaggeration:

but Herod added an oath to it.

The child had done what her mother had told her;

the mother therefore had to be consulted.

Returning immediately, the girl demanded with an imperious and defiant air:

'I will that forthwith thou give me in a dish the head of John the Baptist.'

She would have no delay.

There were plenty of dishes on the table.

The king had only to keep his word.

The command was a hard one.

The tetrarch, sobered now, sees the trick and

realizes the danger.

He feared John;

but a broken oath seemed more to be dreaded

still.

The dancing girl, whom all have applauded, will publicly upbraid him

for breaking his word;

his courtiers will once again smile at his wavering

character which earns him the contempt of Herodias.

Around him stand attendants

waiting to do his commands.

Within a few moments the guard who had acted as

executioner brought to the young girl John's head in a dish.

As M. Fouard has excellently said:

'The shadow into which the prophet desired to sink [Cf.John iii.30.] cloaked his martyrdom.

No witness told how he received the iniquitous command and how peacefully he died.'

[La Vie de N.-S. Jésus-Christ, I, p. 426.]

They could not refuse to allow his disciples to give

him the honours of burial;

these came and took his body and laid it in a tomb.

The Church would pay great honour to that tomb if she knew where it was and

had it in her charge.

In the fifth century it was thought to be at Sebaste

where a church, now a mosque, perpetuates the Baptist's memory.

The most fervent of John's disciples never claimed that their master had risen

from the dead.

The rumours of Herod's court died away along with the tyrant's

remorse.

top

Herod Antipas and the Baptist's death.

In these days, when aberration of critical judgement has gone so far as to

deny the existence of Jesus,

it is worth remarking how the evangelists,

while

they have no pretensions to treat of current history,

are yet in agreement

with what is known of it,

particularly from the historian Josephus.

The Baptist's

death brings Herod Antipas on the scene,

and the tetrarch's character enables

us to appreciate his relations with Jesus;

they were few but significant.

The events of his period of government help us to determine the dates of the

gospel.

Herod Antipas, warned by the disgrace of his brother Archelaus in which he

came near to being involved,

[When Judaea was annexed to the Empire in AD. 6.]

adopted the course of action best calculated

to maintain his position in his little principality.

The chief point was to

win the emperor's favour by an attitude of complete submission.

In this he

showed such assiduity that sometimes the secret information he sent to Rome

anticipated the official reports of the Roman generals on their own operations.

[This is attested in regard to Vitellius by Josephus {Ant.

XVIII, iv, 5).

We refer the reader once for all to the same place for the history of Antipas.

See also Schurer's monograph, Geschlchte des jüdischen Volkes im Zeitalter

Jesu Christi, I, pp. 431-449,

and that of Walter Otto in Pauly-Wissowa's Encyclopedia, Supplement, and fascicule,

articles Herod (18), Herodias, Herod Antipas (24).]

But it was likewise necessary not to give Rome any excuse for intervention

by causing discontent among his own subjects.

Antipas took care therefore to

humour them in their religious beliefs;

whereas his brother Philip, tetrarch

of a country that was more than half pagan, permitted images on his coinage,

Antipas refused to allow this.

He built Tiberias in honour of Tiberius,

but

at the same time he erected a synagogue there.

He was probably punctilious

in going to Jerusalem for the feasts.

Less of an egoist than his father, he

identified himself more than he had done with Judaism, and shared his people's

respect for the Mosaic law and religion.

He was tetrarch of Galilee and Persea,

and thus his realm was exposed on its eastern frontiers to the incursions of

the Nabataean Arabs, whose kingdom was then at its highest pitch of prosperity

under Aretas IV.

Shrewd politician that he was, Antipas had married this king's daughter.

In

a word, all his actions show him to have been a clever schemer, with more prudence

than passion.

He was indeed, in the words of Jesus, a fox. [Luke xiii.32.]

But all his cunning schemes were upset by a fatal infatuation.

While on a

journey to Rome, Antipas paid a visit to his brother Herod:

that is the only

name Josephus gives him, but it would be very strange if he had no other name

to distinguish him from his brother Herods.

This Herod always lived as a private

citizen.

Perhaps he was a man of very mediocre abilities;

at all events he

seems to have been without ambition.

In all probability he had been betrothed

as early as 6 BC. to Herodias, who was a grand-daughter of his father, Herod

the Great, and claimed descent from the Hasmonean line also through her grandmother

Mariamne, the wife so beloved by Herod the Great before he put her to death.

We do not know when that fatal journey occurred;

Otto dates it at the beginning

of the reign of Tiberius, about the year AD.15, or at the very latest before

26, because in that year Tiberius left Rome never to return;

and what was

Antipas going to Rome for except to cultivate the favour of Tiberius?

It may

be, however, that Antipas was received by Tiberius at Capri even after the

emperor's departure from Rome, just as in that island Tiberius received Agrippa

I, the nephew of Antipas;

or Antipas may have contented himself with transacting

his business with Sejanus, the emperor's minister, who was not put to death

until the year 31:

and this is the more likely, seeing that Antipas was later

accused of intriguing with Sejanus.

All things considered, however, the year

26 would well satisfy for the journey, and even for the marriage with Herodias.

At this time she would be over thirty.

[She cannot have been born later than 8 BC. or earlier than

15 BC.

At the betrothal of which we have spoken she would be three or four.]

Antipas conceived for her a violent

passion which blinded him to the consequences.

No doubt she shared the same

passion, but in her it was united with cold calculation, and she demanded the

dismissal of his first wife.

Full of ambition, as she later revealed, she was

determined to be the wife of an independent prince, and his only wife.

It was

arranged that the flight and marriage should take place upon the return of

Antipas.

This was accordingly done, and Josephus

is no less shocked than John the Baptist at this adulterous union, a thing

contrary to all the ancestral laws;

and it was all the guiltier in that

Herodias had a daughter, Salome, by her previous marriage.

[Ant., XVIII, v, 4:

'They have a daughter Salome:

after her birth Herodias, scorning the ancestral laws, married Herod, her husband's

brother, born of the same father, her husband from whom she was separated being

still alive.'

It would be forcing the text to deduce along with Otto that the second marriage

took place immediately after Salome's birth.]

Here we learn

the name of the young dancer mentioned by St. Mark.

Josephus does not give

her age.

[Assuming that her mother married at eighteen, she could

not be more than twenty at this date, AD.29, but might be younger.]

She was still young however, as was the custom of the time, when

she married her uncle Philip the tetrarch of Ituraea, and it was doubtless

shortly before his death, which took place in the year 34, seeing that she

gave him no children.

In all probability it was a marriage of ambition, for

Philip was some thirty years older than she;

that is just what might be expected from the daughter of Herodias and the insolent

girl who demanded the Baptist's head.

But the Nabateean wife of Antipas had no intention of enduring such an insult.

Informed of what was afoot, she had gone to Machaerus and then on to her father

under the pretext of an ordinary visit.

Aretas conceived a violent hatred for

the man who had repudiated his daughter.

Hostilities, however, began over a

quarrel concerning frontiers.

After raids on both sides they came to a pitched

battle.

Antipas was completely routed and sent word of the affair to Tiberius.

Vitellius the legate of Syria received orders to avenge him.

But he, having

no great love for the tetrarch, did not hurry himself, with the result that

the death of Tiberius on March 17, 37, brought matters to a standstill.

It

is in connection with the defeat of Antipas that Josephus mentions John the

Baptist.

Amongst the people, he says, some thought it was a punishment from

God because Antipas, fearing that the Baptist's preaching might end in sedition,

had caused him to be put to death at Machaerus.

[Ant., XVIII, v, 2:

'Now Herod, who feared lest the great influence John exercised over the people

might put it into his power and inclination to raise rebellion (for they seemed

to do anything he should advise), thought it best by putting him to death to

prevent any mischief he might cause, and not bring himself into difficulties

by sparing a man who might make him repent of it when it should be too late.']

Unfortunately the Jewish historian

does not give the date of this important event.

The Jews knew that the wrath of God hangs over the heads of the wicked for

a long time;

so the crime may have preceded the punishment by some years.

Before we compare the reason given by Josephus for John's death with the narrative

of the gospels,

let us see how Antipas was led to his ruin by his weakness

for Herodias.

It was a great mortification for her to see Agrippa, her own

brother, reduced to unfortunate straits on account of his misconduct.

She succeeded

therefore in persuading her husband to give him an honourable position.

[That

of ἀγορανόμος at Tiberias. Ant., XVIII, vi, 2.]

But

a quarrel at table upset all.

While at dinner under the influence of wine,

says Josephus, [ὑπ' οίνον. Ibid.]

the two brothers-in-law fell to insulting one another.

Agrippa

had to go and seek his fortune elsewhere.

He found a brilliant opportunity

in Caligula's friendship, and when Philip the tetrarch died, that emperor gave

the tetrarch's realm with additions to Agrippa along with the title of king.

Herodias could not endure that her husband should remain a mere tetrarch while

another member of his family wore the royal diadem.

By dint of entreaties,

for Antipas was no contemptible slave of a frowning woman, she persuaded him

to go and ask the young emperor for the same favour.

But Agrippa had not forgiven,

and a denunciation of Antipas reached Baiae, where Caligula then was, at the

same time as the two petitioners, namely, the tetrarch and his wife.

Antipas

was stripped of his dominions, which were bestowed on Agrippa, and exiled to

Gaul

[To Lugdunum, not Lyons but Lugdunum Convenarum,

or St. Bertrand-de-Comminges. Cf. Ant., XVIII, vii, 2, with Bellum,

II, ix, 6.]

whither Herodias, faithful in misfortune, accompanied him.

Clearly this account by Josephus owes nothing to the gospel, but neither do

the evangelists depend on the Jewish historian, so different is the view of

the Baptist's death in each case.

Yet their agreement is beyond question:

the marriage of Antipas with his brother's wife, contrary to the Law;

the

existence of a daughter of the first marriage of Herodias;

the influence of

Herodias over her husband, though he was sometimes refractory;

the tetrarch

losing his common sense under the influence of drink;

his regard for the Jewish

religion when not carried away by passion;

and finally the death of the Baptist, an intrepid preacher of

repentance.

There is very little therefore for captious critics to lay hold

of: in fact two points only.

First, Mark gives the name Philip to the first

husband of Herodias.

He is accused of having confused him with Philip the

tetrarch.

Certainly some Christian interpreters of the gospel of St. Mark

have fallen into that error,

[This is the case with the Slavonic version ofJosephus,

on which it would not be safe to rely in order to defend Mark against the Greek

of Josephus. Cf. Berendts, Die Zeugnisse vom Christentum im slavischen

'De Bello Judaico des Josephus,' in Texte und Untersuchungen,

N.F. XIV, 4 (1906), p. 7 ff. and 33.]

and have interpolated one version of Josephus

accordingly;

but Mark makes no such mistake, for he says nothing of Philip

the tetrarch.

Luke mentions him [Luke iii.1.],

but his gospel was later than Mark's.

The

fact is that the plain Herod of Josephus must have had another name also,

and may have been called Philip like his brother.

The case was not uncommon

in the Hellenistic period:

Antipas had a brother named Antipater, which

is the same name. [Cf. Otto, loc, cit., p. 159.]

But this point is of no consequence.

What is more serious

is the fact that, according to Josephus, Antipas took proceedings against

John of his own accord, as a political measure:

the verdict of the critics

is that the whole story in the gospels about the banquet is a mere fiction.

Schtirer and Otto, however, who accept the story, find no difficulty in admitting

that the two reasons for John's death are perfectly reconcilable, a fact

that is fairly obvious.

But we should go further still and maintain that

without Mark's account the facts cannot be properly understood.

Let us first observe a point made by Otto.

For the successors of Herod the

Great, Josephus can no longer draw upon histories of particular individuals,

like that of Nicholas of Damascus which he had used for the first Herod:

he

writes with the aid of a universal history and 'in aphorisms.' [Ganz

aphoristisch, Otto, p. 172.]

One of these

aphorisms or cliches is the hackneyed attribution of events to 'revolutionary

innovations.'

If we may believe Josephus,

Herod had John taken away to Machaerus:

Herod had John taken away to Machaerus:

and this is very probable.

The presence of John in Galilee, even in prison -

or

rather, especially in prison -

was likely to stir up those in his favour.

At

Machaerus, Antipas was at his ease.

The fortress had been built by Herod the

Great who, in the early days of his reign, had felt the need of a place of

refuge for his wives and his treasure till better

times came.

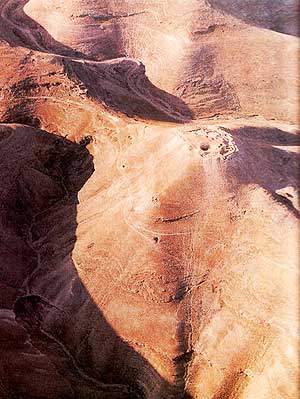

It was a regular den of brigands.

The ruins, still known as Mekawer,

lie to the east of the Dead Sea almost opposite Hebron;

the place stands

on about the same level as the plateau further east, but is divided from

it by a deep and precipitous valley.

[Cf. Une croisière autour de la Mer Morte, by Abel,

O.P., pp. 30-41.]

Antipas had only to leave John to end

his days in some dungeon, for the tetrarch was not cruel by disposition.

Indeed, but for the influence of Herodias,

would he even have had John imprisoned?

Critics who admit the main facts of the life of Our Lord -

and there are few

who do not -

cannot find any explanation of the relations of Antipas with Jesus

if they hold that his attitude towards the Baptist is sufficiently described

by what we read in Josephus.

Would one and the same man really have behaved

towards John with such senseless cruelty and merely out of arbitrary precaution,

yet have shown such great tolerance in the case of Jesus, a tolerance moreover

that was mingled with an amused curiosity and not particularly disagreeable?

Josephus knows that the marriage of Antipas met with disapproval.

There is

nothing surprising, therefore, in the fact that John should have voiced that

disapproval.

Herodias had obtained the dismissal of her rival, in spite of

the risk of serious ensuing difficulties.

She could not suffer her marriage

to be condemned and even endangered in the name of Jewish traditional law.

John's protest was not long in coming, and for that reason it seems to us

the marriage took place in the year 26, the nearest date to the year in which,

according to St. Luke [Luke iii.1.], the Baptist

began his ministry, namely 27, and the nearest also to the defeat of Antipas

in the year 36.

Herod had incurred

the displeasure of Aretas, and he saw threats of war arising on his eastern

frontier.

Herodias was now in his possession, and he had kept his word that

he would have no other wife.

He would surely have hesitated to incur the

displeasure of his own subjects, in addition to that of Aretas, by dealing

harshly with John.

But after he had been incensed by John's rebuke to him

in person and urged on by his wife, he decided to put this troublesome individual

in a secure prison.

Herodias saw that this was as much as she could win from

him;

she therefore had recourse to stratagem, along with the aid of lust

and wine.

She seized a favourable opportunity, the only one she had, when

Herod went to Machaerus to organize the defence of the frontier;

for there

he thought that the crime she desired could be accomplished almost in secret.

Thus, far from being contradictory, the two accounts of John's death are rather

complementary and in a most convincing way.

Some vague political excuse provided

the simplest explanation of the murder for an historian not fully informed

of the facts.

But the true motive springs from the character that Josephus

himself has drawn of the tetrarch;

a prudent ruler, friendly to everybody,

when not led astray by his wife or besotted by wine.

We can confidently rank

the Baptist's death amongst the deeds of which the circumstances, whether public

or hidden, are best known to us.

top