PART I

CHAPTER 31

![]() LISTEN

to the Mirfield Community chant the Agnus Dei. Music details HERE.

LISTEN

to the Mirfield Community chant the Agnus Dei. Music details HERE.

PROPITIATION AND FORGIVENESS

HOME | contents | propitiation | forgiveness | what we see in the crucifixion

I. Propitiation

The word propitiation (ἱλασμός)

occurs in the New Testament only twice (I John 2.2,

4.10),

and the similar word ἱλαστήριον once

(Rom.2.25).

If we are to understand it,

we must go behind the Latin and even the Greek

to the Hebrew the language in which both St. Paul and St. John thought.

It represents the Hebrew "kapper"

which means, not to induce one who is angry to relent

(which is what we usually mean by propitiation),

but to change from outside that which causes anger.

Our Lord is the propitiation for our sins (I John 2.2)

that is, God is angry with us because of our sins,

but our Lord takes away our sins

so that His Father will be angry with us no more.

He does this, as we have seen in the last chapter,

by breaking the power of sinful habit (the flesh),

sinful association (the world),

and sinful control over us (the Devil),

and by building up in us,

by means of the Holy Ghost,

His new and risen life.

He changes, not God, who does not change,

and who loves us perfectly in spite of all our sins,

but US, so that we no longer incur God's anger but become fit for union with

Him.

But all this is not what we commonly mean by propitiation,

and it is most unfortunate that this word should have become the recognized

translation of ἱλασμός.

It was commonly taught in the Middle Ages that our Lord's Death was intended

to propitiate God,

to offer Him something in compensation for what He had

lost through our sin;

and the sacrifice of the Mass which became so dominant

in popular religion was regarded as a propitiation in this sense, almost

such a propitiation as the King of Moab made when he offered his son as a

sacrifice to Chemosh to drive away the invaders of his country (II Kings

3.27).

Against such a notion the Reformers were right to protest.

But no intelligent Christian today believes that either the death of Christ

or the Eucharist is a propitiation in this sense.

Unfortunately, many ill-informed people still think that this is what the

Mass means.

It is this that they reject when they reject the Mass (see, for instance,

Bishop E. A. Knox, Sacrament or Sacrifice).

The attack upon "the sacrifices of Masses" in Article 31 (see the

note at the end of the last chapter) depends on the word "wherefore".

Because it is by Christ's offering only that we are saved and our sins are

removed, the idea that we need also to

"propitiate" or bribe God by offering the Eucharist in order to

obtain redemption is false and dangerous.

It is in this sense only that the Anglican Communion rejects "the sacrifices

of Masses".

The Council of Trent defined the Eucharist as

"a true, proper, and propitiatory sacrifice".

This definition is true if "sacrifice" means offering (not immolation

or slaying),

and if "propitiatory" means removing the sins of men;

for the Eucharist of Mass is the means by which the faithful on earth are

enabled to share in the perpetual self-offering of our Lord in heaven.

But

it is very doubtful whether the Council of Trent or its representatives today

would accept this interpretation.

It is precisely because the Anglican Communion rejects the belief in sacrificing

priests in the popular medieval sense, and has carefully removed the references

to sacrifice from the Ordinal in order to avoid that sense, that the Papacy

says that it refuses to recognize Anglican ordinations (the real reason is

probably one of policy rather than of doctrine: see p. 399).

The last chapter contained a summary of several theories of the way in which

our Lord by His death and resurrection freed us from the power of sin.

But we also have to be freed from the guilt of sin.

top

II. Forgiveness

God in Christ hath forgiven you

(Eph.4.32).

The forgiveness of God is not a legal or forensic process.

It cannot be understood in terms of justice and reward but only in terms

of love.

God HAS forgiven us,

and all guilt is wholly wiped away by His pardon.

But our repentance is the condition of our pardon,

for otherwise pardon would be immoral.

Even the Prodigal Son in the parable, whose repentance was superficial, perhaps

even pretended (for his reason for returning was that his father's slaves

were well fed, whereas he was living on pigs, food), must be supposed to

have been brought to real repentance by his father's love. [Luke

20.11-24.]

We cannot, indeed, build our doctrine of forgiveness wholly on this parable,

which like most of our Lord's parables, is meant to illustrate only one point.

The punishment that we have to suffer is not intended to satisfy justice

but to reform us.

We cannot be freed from our bad habits and desires without pain.

This pain, if it is used rightly, will purify us.

Experience shows that pain is required for the development of character;

especially character that has been marred.

And since it is required in this life,

it is at least possible that it may be required hereafter.

We have not, in most cases, got rid of the "old man" when we die.

It is reasonable to suppose that the process will continue after death.

But this opinion (only an opinion, for there is no basis for it in Scripture)

is very different from the "Romish doctrine of purgatory" (Article

22), according to which every sin that we commit must receive retribution

in this life or the next (see pp. 438-40).

top

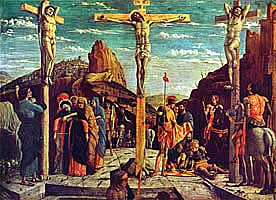

III. What we See in the Crucifixion

We may close this subject with the consideration of what we see

when we look on the crucifix on the figure of the Son of God dying for us.

We

see first the love of God for man,

which is most completely displayed in the death of God the Son.

He loves us not for what we are but simply because He is Love.

Second, we see the righteousness of God, His hatred of sin.

He hates it so much that He gave His life to save us from it.

Third, we see more clearly than anywhere else the real nature of sin.

The disobedient will comes to hate God.

When it was confronted with perfect Goodness, it crucified Him.

It was no mere mistake, no "undeveloped form of good?,

which brought our Lord to His death.

It was diabolical hatred, cruelty, and jealousy.

We can see it still in the world, indeed ruling over a large part of the

world.

We can feel it in ourselves if we know ourselves.

It was this, which our Saviour came to destroy,

and which we, as His soldiers and servants, are pledged to help Him to destroy.

top