And watch the girls (wow!!!) of Wheaton College Women's Chorale sing Greene's 'Like as the Hart' HERE.

After the death of Purcell there is a growing gap in English music – filled largely by an influx of foreign musicians: an ever-increasing flood, which established the sense of inferiority in British music for the next 170 years. Handel, who was ten years old at Purcell's death, was to be the greatest of these invaders, and a very mixed blessing for English music. His massive religious writings however are not part of our present national story, although of course, many pieces of his oratorios have a permanent place in our church repertory.

This was a great age of opera; most of it Italianised, and much in doubtful taste. Typical and indicative of the times was the growing popularity of that black sheep of musical art–the virtuoso singer. With church music only a few names appear throughout the century to maintain a declining tradition.

WILLIAM CROFT(died 1727) and MAURICE GREENE(died 1755) were foremost in the early years. The former will be long remembered for his hymn-tunes St. Anne ("O God our help") and Hanover ("O Worship the King"), but both produced many anthems and service-settings which are heard today, and still worth hearing. Scholarly, and attractive as these are, they frequently lack vitality and personal depth of feeling. The range too, is far narrower than Purcell's, although occasionally, as in Greene's "Lord, let me know mine end," the greater man's work is well maintained.

![]() Listen

to Croft's St Anne - "O God our help in Ages Past" sung by King's College

Choir. Music details HERE.

Watch this hymn sung at First Plymouth Church, Lincoln, Nebraska HERE.

Listen

to Croft's St Anne - "O God our help in Ages Past" sung by King's College

Choir. Music details HERE.

Watch this hymn sung at First Plymouth Church, Lincoln, Nebraska HERE.

![]() Listen

to Crofts Hanover - "O Worship the King",

sung by the Paisley Abbey Choir. Music details HERE.

Listen

to Crofts Hanover - "O Worship the King",

sung by the Paisley Abbey Choir. Music details HERE.

![]() Listen to "Magnify his Name" by Maurice Greene. Music details HERE.

Listen to "Magnify his Name" by Maurice Greene. Music details HERE.

![]() Watch the choir of New College, Oxford sing Green's harvest anthem 'Thou visitest the Earth' HERE.

Watch the choir of New College, Oxford sing Green's harvest anthem 'Thou visitest the Earth' HERE.

And watch the girls (wow!!!) of Wheaton College Women's Chorale sing Greene's 'Like as the Hart' HERE.

WILLIAM BOYCE,

Picture

– Dr William Boyce (1710-1779)

quite a considerable composer,

showed a grace and lightness of touch that will keep his name alive in church

music,

as it will live outside for his composition of "Heart of Oak."

He, at all events, was aware of the tragedy which neglect was bringing to

Picture

– Dr William Boyce (1710-1779)

quite a considerable composer,

showed a grace and lightness of touch that will keep his name alive in church

music,

as it will live outside for his composition of "Heart of Oak."

He, at all events, was aware of the tragedy which neglect was bringing to

Thanklessly completing the work begun by Greene, he published his Cathedral Music– four volumes of the best sacred music of the previous two centuries. When Boyce died in 1779, there was darkness indeed in the English choral art.

![]() Listen

to Boyce's "Blessed be the Name of the Lord",

sung by St Paul's Cathedral choir. Music details HERE.

Listen

to Boyce's "Blessed be the Name of the Lord",

sung by St Paul's Cathedral choir. Music details HERE. ![]() Watch Jubilate sing Boyce's 'Alleluia Canon' HERE.

Watch Jubilate sing Boyce's 'Alleluia Canon' HERE.

Nevertheless, there was one redeeming feature of this century. As the hymn and the Anglican chant grew in popularity, it was on these very miniature forms of composition that the whole reputation of eighteenth-century music virtually rests. The Hymn-tunes and chants of CROFT, GREENE and BOYCE, together with those of BATTISHILL, TOPLADY, WATTS, and many others within and outside the established church, frequently achieve perfection, and our hymnals and psalters would be much poorer without them.

![]() Listen

to the choir of St Paul's cathedral sing Battishill's anthem "O Lord Look

"Music details HERE.

Listen

to the choir of St Paul's cathedral sing Battishill's anthem "O Lord Look

"Music details HERE.

![]() WATCH Lincoln Cathedral choir chant psalm 104 (Battishill chant) HERE.

WATCH Lincoln Cathedral choir chant psalm 104 (Battishill chant) HERE.

![]() Listen

to the Kenton Sunday School choir & USAF Protestant Chapel choir, West

Ruislip, sing Buck & Toplady's "Rock of Ages." Music

details HERE.

Listen

to the Kenton Sunday School choir & USAF Protestant Chapel choir, West

Ruislip, sing Buck & Toplady's "Rock of Ages." Music

details HERE.

![]() Listen

to the choir of King's College, Cambridge, sing "When I Survey the Wondrous

Cross", Watts & Miller. Music details HERE.

Listen

to the choir of King's College, Cambridge, sing "When I Survey the Wondrous

Cross", Watts & Miller. Music details HERE.

![]() WATCH King's College choir sing the hymn 'When I survey' (tune: Rockingham) HERE.

WATCH King's College choir sing the hymn 'When I survey' (tune: Rockingham) HERE.

There was indeed a tendency for all music–including the larger church forms– to become hymn-like in conception. The composers of anthems employ largely a note-for-syllable style, with voice parts moving chiefly in chordal sequence– a great contrast to the intricate texture of the earlier polyphony. Such music is not necessarily inferior to any other, but has obvious restrictions in breadth and variety of expression. The work of ill-equipped imitators of Handel, combining with this natural tendency,

But English music could not hope to thrive in such a century. It was a period of wit and finery in the cities (and of unspeakable squalor in the country): an age of the coffee-house which produced poets like Prior, Gay and Pope – poets whose great lack was that depth of human feeling that produces good music: a self-satisfied era which considered Shakespeare an uncouth yokel, and sought its pleasures in shallow imitations of the ancients. The masterpieces of Byrd, Farrant, Gibbons and Purcell had no place in such a society and were forgotten. A sad century indeed for church music, made sadder by the thought of Haydn's and Mozart's work in the same period.

| Croft | God is gone up | Novello |

| Te Deum from Service in A | Novello | |

| Greene | Lord, let me know mine end | Novello |

| Let God arise | Novello | |

| Thou visitest the earth | Novello | |

| Boyce | Save me O God | Novello |

| By the waters of Babylon | Novello | |

| Lord, what is man | Novello | |

| Te Deum in C | Novello | |

The century opened with no improvement. The old patronage for church composers was gone, and increasing public audiences tempted composers to write profitable secular trivialities. Mediocre imitations of Handel's choral music became the established church fashion.

ATTWOOD(1765-1838) and CROTCH(1775-1847) however are rightly recalled in the continued use of their anthems and service-settings. Attwood was an esteemed pupil of Mozart, and later a friend of Mendelssohn, with whom the "second Handel" lived for a while. JOHN GOSS and WILLIAM WALMISLEYwere worthy successors, but restricted by the low creative vitality of the age.

![]() Listen

to the choir of St Paul's sing Psalm 92 to Crotch's chant. Music details HERE.

Listen

to the choir of St Paul's sing Psalm 92 to Crotch's chant. Music details HERE.

Listen to the choir of St Paul's

cathedral sing Thomas Attwood & William Walmisley's D minor setting of

![]() the

Magnificat,

&

the

Magnificat,

& ![]() the

Nunc Dimittis. Music details HERE.

the

Nunc Dimittis. Music details HERE.

![]() Watch the choir of Somerville College, Oxford sing Attwood's anthem 'Teach me, O Lord' HERE.

Watch the choir of Somerville College, Oxford sing Attwood's anthem 'Teach me, O Lord' HERE.

![]() Listen

to the choir of King's college, Cambridge sing Lyte & Goss's Hymn,

"Praise my Soul the King of Heaven." Music details HERE.

Listen

to the choir of King's college, Cambridge sing Lyte & Goss's Hymn,

"Praise my Soul the King of Heaven." Music details HERE.

![]() Watch the choir of Saint Clement's Church, Philadelphia sing Goss's 'See amid the Winter Snow' HERE.

Watch the choir of Saint Clement's Church, Philadelphia sing Goss's 'See amid the Winter Snow' HERE.

![]() Watch the Kampen Boys choir chant Walmisley's Mag & Nunc HERE.

Watch the Kampen Boys choir chant Walmisley's Mag & Nunc HERE.

The works of these four men are unpretentious, but they have a high degree of dignity, charm and approptiateness that justifies their continued popularity.

SAMUEL WESLEY was capable of much fine work, and his son SAMUEL SEBASTIAN is still justly heard – and commendable for his long and gallant fight against the church authorities for their neglect of music and musicians. HENRY SMART(1810-1879) and W T BEST(1826-97) had a pureness of quality that keeps their work alive. STAINER(1840-1901) and STERNDALE BENNETT (1816-75) would have been considerable composers in any other age, but FREDERICK OUSELEY is more often heard now, having avoided many of the sugary pitfalls into which they, fell, and showing at least a sense of pure craftsmanship.

![]() Listen

to the choir of St Paul's sing Ouseley's "O Saviour of the World." Music

details HERE.

Listen

to the choir of St Paul's sing Ouseley's "O Saviour of the World." Music

details HERE.

![]() Watch these combined choirs sing Henry Smart's Magnificat in B flat at St. Stephen's Pro-Cathedral, Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania HERE.

Watch these combined choirs sing Henry Smart's Magnificat in B flat at St. Stephen's Pro-Cathedral, Wilkes-Barre, Pennsylvania HERE.

![]() Listen

to the choir of St Paul's sing Psalm 77 in Stainer's chant. Music details HERE.

Listen

to the choir of St Paul's sing Psalm 77 in Stainer's chant. Music details HERE.

![]() Watch the choir of Somerville College, Oxford sing S S Wesley's anthem 'Lead Me Lord' HERE.

Watch the choir of Somerville College, Oxford sing S S Wesley's anthem 'Lead Me Lord' HERE.

Surveying the first seventy years of the nineteenth century is a disheartening task – not so much that the composers we have mentioned were limited in their achievements, but because the remainder, a far larger "number, were so artistically perverted, and had such a wide following. The publication of Hymns Ancient and Modern in 1861 probably places the whole temper of the century: a certain amount of creditable scholarship, but marred time and time again by squeamish sentimentality. STAINER, DYKES and MONKwere among its foremost contibuters, and better than many.

![]() Listen

to The choir Of King's College, Cambridge sing Dykes' "Holy,Holy,Holy,

Lord God Almighty." Music details HERE.

Listen

to The choir Of King's College, Cambridge sing Dykes' "Holy,Holy,Holy,

Lord God Almighty." Music details HERE.

The reasons for this poor state of church music: –

| Attwood | Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis in C | Novello |

| Turn Thy face | Novello | |

| Crotch | Comfort, O Lord | Bosworth |

| Bosworth | How dear are Thy counsels | Novello |

| Goss | Service in A | Novello |

| I will magnify thee | Novello | |

| Come, and let us return | Novello | |

| Walmisley | Magnificat and Nunc Dimittis in D minor | Novello |

| From all that dwell | Novello | |

| S. S. Wesley | Wash me thoroughly | Novello |

| Smart | The Lord is my Shepherd | Novello |

| Be glad, O ye righteous | Novello | |

| Ouseley | Service in D | Novello |

| O Lord, Thou art my God | Novello | |

| Walmisley | Nunc Dimittis in D minor | H.M.V. B 9308 | mag & nunc | |||

| Walmisley | Magnificat in D minor | Columbia 9147 | ||||

| S.S. Wesley | Thou wilt keep him | H.M.V. RG 9 | Thou wilt ... |

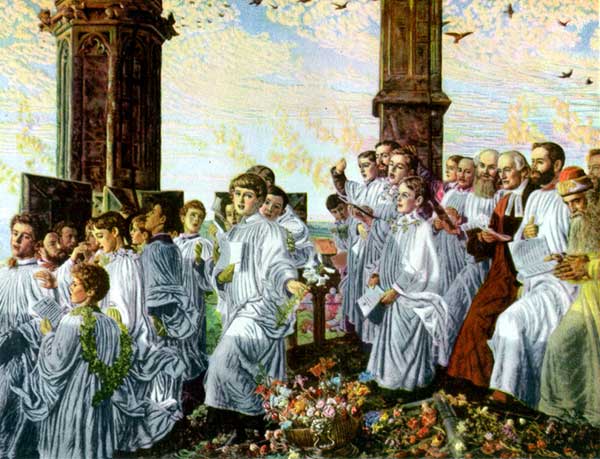

"May Morning on Magdalen Tower." Oil painting. Holman

Hunt.

"English Music" W J Turner. William Collins, 1945.

The dawn broke before the century was through. HUBERT PARRY(1848-1918), C V STANFORD(1852-1924) and C H LLOYD(1849-1919) produced, almost suddenly, music that was once again worthy of the old heritage of Tallis, Byrd, Gibbons, and Purcell. Slowly the British people began to regain a taste for something better than The Crucifixion, and its lesser counterparts.

![]() Listen

to the choir of St George's Chapel sing Parry's "My Soul, There is a Country."

Music details HERE.

Listen

to the choir of St George's Chapel sing Parry's "My Soul, There is a Country."

Music details HERE.

![]() Listen

to the choir of St Paul's sing Stanford's chant to Psalm 150. Music details HERE.

Listen

to the choir of St Paul's sing Stanford's chant to Psalm 150. Music details HERE.

Typical of this new era is Parry's Blest Pair of Sirens, a perfect eight-part setting of Milton's perfect poem. It is a superbly sustained piece of polyphonic writing with a great freshness and sincerity in its thrilling climaxes.

A good example of Stanford's work is his service setting in C major. The opening, bars of the Magnificat are like the sudden drawing aside of curtains, letting in pure sunlight where the musty dimness of Victorianism recently reigned.

![]() Listen

to the choir of St John's College, Oxford, sing Stanford's Magnificat in C.

HERE.

Listen

to the choir of St John's College, Oxford, sing Stanford's Magnificat in C.

HERE.

Lloyd, sound though not spectacular, still finds frequent place in our services.

The awakening, of course, was part of a national stirring of mind and spirit. With the approach of the new century there grew up something akin in spirit to the expansive and inspiring years of the Tudor monarchs.

Musically there were many factors of the times having particular influence:

They are given in chronological order with the decades in which

1850-60 |

Edward Elgar, Basil Harwood. |

1860-70 |

W. G. Alcock, Alfred Hollins, Granville Bantock, Richard Terry, Charles Wood, Walford Davies, Tertius Noble. |

1870-80 |

Percy Buck, Vaughan Williams, Edward Bairstow, Harvey Grace, Gustav Hoist, Sydney Nicholson, Martin Shaw, Roger Quilter, Thomas Dunhill, Rutland Boughton, Stanley Roper, Harry Farjeon, Frank Bridge, John Ireland, Geoffrey Shaw |

1880 onwards |

W. H. Harris, George Dyson, H. G. Ley, Herbert Howells, Harold Darke, R. O. Morris, Thomas Wood, E. J. Moeran, Percy Whitlock, Ernest Bullock, Eric Thiman, and many others. |

Among these names are many who in larger fields of the choral and orchestral art gave Britain once again an international pride in her music. Collectively, and with other purely secular writers, they form beyond doubt the healthiest and most virile national school of composers in present times.

Up to the age of Purcell, music had chiefly existed in the smaller forms such

as the church service provided.

Today the range is infinitely wider and more attractive.

However, many of this new English school found their training-ground in church

composition,

and not a few have discovered in it their specialised medium.

Although faults are present in their work, none has suffered from those lapses

in taste and craftsmanship which preceding decades so misguidedly applauded.

All have added appreciably to the glorious tradition of English church music.

The full story of these great achievements belongs to the present century. Before a quarter of it was passed the tide of fine new church music was at the flood, and although composers tend more and more towards the bigger forms in music, there is no reason to suppose that this new peak in English church writing has passed with the approach of the half-century.

All our present church music is not perfect. Much of it still has traces of the academic flavour of lesser ages. However, as at previous points in history, the steady influx of lively secular styles can improve it considerably, and expanding public interest in secular music will have an increasing effect. Good and living music in the church will be demanded by future congregations.

The church, rightly and of necessity, is slow to change. And although it has been often tardy in receiving these valuable new gifts, considerable progress has been made, and at least the larger religious institutions are today as good musically as they ever were. Where churches still remain backward, however, the fault is certainly a local one due to their own insufficiency. The Royal School of Church Music, founded in 1928 by Sir Sydney Nicholson, has given further opportunity for the new (and the best of the old) music to spread throughout the land.

The present chapter has recalled two recurrent historical problems that may appear still unsolved.

The danger of highly specialised music is discouraging congregations from active participation in the services.

The extent to which secular influences are desirable.

From our study of the past and present, however, the answer is near at hand:

We can expect congregations to "lag behind" a progressive movement in church music; but that lag will become ever shorter as musical and general education advances.

Secular influences are always welcomed if they bring with them something of that art which elevates the spirit. Everything that is best should find its place in church music.

In any case the church service wisely provides for all manner of men. The division of services into choral and congregational elements, as at present, is admirable, and has complete precedent in the earlier climaxes of English music. But let also the simple congregational parts, the hymns, responses, and chanting be vital and (consequently) artistic. There is nothing to prevent their being equally as inspiring as an anthem sung in the chancel.

| G Parry | My soul, there is a country | Deane & Sons |

| Hear my words | Novello | |

| Service in D major | Novello | |

| Stanford | Be merciful | Stainer & Bell |

| Service in C | Stainer & Bell | |

| Walford Davies | King of Glory | Curwen |

| God be in my head | Novello | |

| Elgar | Fear not, O land | Novello |

| Doubt not thy Father's care | Novello | |

| Benedicite | Oxford | |

| Vaughan Williams | Let us now praise famous men | Curwen |

| Holst | Festival Te Deum | Stainer & Bell |

| Christmas Day | Novello | |

| G Shaw | Dawn draws on | Novello |

| The spacious firmament | Edward Arnold | |

| Dyson | Three Songs of Praise | Novello |

| Valour | Edward Arnold | |

| Darke | Benedictus in F major | Stainer & Bell |

| Kitson | How sweet the Name | Stainer & Bell |

| Bullock | Give us the wings of faith | Oxford |

| Howells | Here is the little door | Stainer & Bell |

| Thiman | O Lord, support us | Novello |

| Whitlock | Communion Service | Oxford |

| Stanford | Gloria in Excelsis | HMV RG 12-13 | Gloria | |||

| Te Deum (in B flat) | HMV C 2448-9 | Te Deum | ||||

| Magnificat in G | Columbia 9147 | Mag in G | ||||

| Walford Davies-Attwood | Magnificat | HMV B 9308 | Psalm 121 | |||

| Walford Davies | Be strong | HMV RG 7 | God be in my Head | |||

| O little town of Bethlehem | HMV B 4285 | O Little ... | ||||

| Vaughan Williams | Kyrie in G minor | HMV DB 1786 | Mass ... | |||

| Te Deum | HMV RG 13-14 | |||||

| Bullock | The Lord send you help | Decca R 001 | ||||

| Bullock (arranged) | Veni Creator (plainsong hymn) | HMV RG 4 | ||||